NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

GOVERNMENT DISTORTION IN INDEPENDENTLY OWNED MEDIA:

EVIDENCE FROM U.S. COLD WAR NEWS COVERAGE OF HUMAN RIGHTS

Nancy Qian

David Yanagizawa-Drott

Working Paper 15738

http://www.nber.org/papers/w15738

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

February 2010

This paper supersedes the previous version entitled, “Watchdog and Lapdog...”. We are indebted to

Matthew Gentzkow, Mikhail Golosov and David Stromberg for their many thoughtful comments;

Abhijit Banerjee, Stefano DellaVigna, Raquel Fernandez, Dean Karlan, Brian Knight, Michael Kremer,

Justin Lahart, Suresh Naidu, Nathan Nunn, Torsten Persson, Jesse Shapiro, Jakob Svensson and Chris

Udry for their insights; and the seminar participants at Stanford University, Yale University, New

York University, Boston University, the University College of London, Stockholm University IIES,Warwick

University, Universitat de Pompeu Fabra, Paris School of Economics, Universitet du Toulouse, McGill

University, NBER Summer Institute Political Economy, BEROC, BREAD CIPREE and NEUDC

for useful comments; and Carl Brinton and Aletheia Donald for invaluable research assistance. All

mistakes are our own. Comments or suggestions are very welcome. The views expressed herein are

those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-

reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official

NBER publications.

© 2010 by Nancy Qian and David Yanagizawa-Drott. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not

to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including

© notice, is given to the source.

Government Distortion in Independently Owned Media: Evidence from U.S. Cold War News

Coverage of Human Rights

Nancy Qian and David Yanagizawa-Drott

NBER Working Paper No. 15738

February 2010, Revised September 2013

JEL No. L82,P16

ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the extent to which strategic objectives of the U.S. government influenced

news coverage during the Cold War. We establish two relationships: 1) strategic objectives of the

U.S. government cause the State Department to under-report human rights violations of strategic allies;

and 2) these objectives reduce news coverage of human rights abuses for strategic allies in six U.S.

national newspapers. To establish causality, we exploit plausibly exogenous variation in a country's

strategic value to the U.S. from the interaction of its political alliance to the U.S. and membership

on the United Nations Security Council. In addition to the main results, we are able to provide qualitative

evidence and indirect quantitative evidence to shed light on the mechanisms underlying the reduced

form effects.

Nancy Qian

Department of Economics

Yale University

27 Hillhouse Avenue

New Haven, CT 06520-8269

and NBER

David Yanagizawa-Drott

79 JFK Street

Cambridge, 02138 MA

USA

1 Introduction

Mass media plays a powerful role in society. It reaches an immense audience, and its content

can affect a wide range of outcomes, including political behavior such as voting.

1

In democratic

regimes such as the United States, the importance of the media is reflected in its being called the

fourth estate, which is supposed to report on the activities of the government in the interest of the

public and act as a “watchdog” of democracy. However, the ability of the media to perform its

prescribed role has come under question as observers point to an increasing number of instances

when media content is distorted by the government. Numerous books written by political scientists

and former journalists voice this concern. Prominent examples include Bennett, Lawrence, and

Livingston (2008), Cook (1998) and Thomas (2006).

2

The examples of government distortion come

from many different time periods, including the war with Vietnam during the 1960s, interventions in

Central America during the 1980s, as well as the recent war with Iraq that began in 2003 (Bennett,

Lawrence, and Livingston, 2008). Bennett, Lawrence, and Livingston (2008, p. 8) summarizes

the motivation behind these concerns: “The democratic role of the press is defined.. by those

moments when government deception or incompetence compels journalists to find and bring credible

challenges to public attention and hold rulers accountable... This accountability function of the

U.S. press has been weakened in the contemporary era, and its standing is sorely in need of greater

examination”. Similarly, in her textbook, Mass Media and American Politics, Graber (2006) urges

a closer examination of the political economy of media with a quote from Joseph Pulitzer, “An able,

disinterested, public-spirited press, with trained intelligence to know the right and courage to do

it, can preserve that public virtue without which popular government is a sham and a mockery...

The power to mould the future of the Republic will be in the hands of the journalists of future

generations”, to which Graber follows with, “How well is the U.S. press meeting [this challenge]?”

Graber (2006, p.20).

3

This paper attempts to make progress on this important question by assessing the extent of

1

Recent studies have shown that media can affect voting behavior (e.g., Prat and Stromberg, 2005; Gentzkow,

2006; DellaVigna and Kaplan, 2007; Chiang and Knight, 2011; and Enikolopov and Zhuravskaya, 2011), other

political behavior (Paluck, 2008; Gerber, Karlan, and Bergan, 2009; Olken, 2009), and social outcomes such as

literacy (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2008a) female empowerment (Jensen and Oster, 2009) and fertility (La Ferrara,

Chong, and Duryea, 2008).

2

See the works referenced in Bennett, Lawrence, and Livingston (2008) and Cook (1998) for the large body of

work about the media and the U.S. government from media and political science scholars.

3

The quote from Pulitzer was originally printed in the North American Review (1904).

1

government distortion of the news in the United States. Our study aims to determine whether the

anecdotal and case evidence on government manipulation reflects isolated incidents or whether they

reflect systematic distortion that could be a symptom of deeper and more fundamental concerns.

In other words, we ask whether a democratic government can systematically distort news coverage

from independently owned outlets. With the exception of Besley and Prat (2006), this question has

not yet been rigorously studied.

4

For practical reasons that we discuss later, we focus on human

rights news coverage during the latter period of the Cold War.

Our study proceeds in three steps. First, to motivate our investigation, we document that the

U.S. government often attempted to manipulate news coverage of human rights practices of their

political allies during the Cold War. We rely on qualitative evidence from political scientists as well

as internal government memos that explicitly state government objectives and tactics for a large

number of cases. These memos, which are typically not available to the public, were declassified

as part of the Iran-Contra investigation. The availability of rich case evidence is the one of the

advantages of focusing on the Cold War era.

Second, we combine the recent theories of endogenous news coverage developed by Prat and

Stromberg (2005, 2011) and Stromberg (1999, 2004a, 2004b) with a theory of media manipulation

by Besley and Prat (2006) to develop a framework for understanding government manipulation in

our context. In our model, domestic voters care in part about the foreign policy pursued by the

U.S. government. Voters cannot directly and fully evaluate the foreign policy (preferences) of the

incumbent and partly base their inferences on the behavior of allied foreign countries that vote

with the United States in the United Nations (UN). News reports about human rights violations of

allies serve as indicators of U.S. foreign policy and affect the probability that the incumbent U.S.

government will be voted out of office. We assume that “worse” countries are more likely to commit

human rights violations and are more likely to vote with the United States if the U.S. government’s

foreign policy is “bad”. U.S. voters observe voting behavior and read about human rights violations

to make their inferences about the U.S. government’s type. There are two groups of voters. The first

group has broad interests, reads the news about all foreign countries and make inferences based on

the behavior of all countries. The second group is only interested in the countries that are currently

4

A recent working paper by Gentzkow, Petek, Shapiro, and Sinkinson (2012) examines the historical U.S. context.

We discuss this study more later in the introduction.

2

on the UNSC. That voters infer the quality of government policies from news reports and the insight

that newspaper coverage affects the posterior beliefs of the voters about the quality of those policies

is very similar to the framework in Durante and Knight (2012).

It follows that obtaining a seat on the Security Council generates two opposing effects on U.S.

news coverage of the human rights practices of foreign countries: i) the demand effect, an increase

in coverage when countries become Council members because more readers are interested; and ii)

the distortion effect, a reduction in coverage due to the incentives of the government to manipulate

the media. Since there are many fewer countries on the Council than not on the Council (e.g., in

the UN General Assembly), it is cheaper for the U.S. government to manipulate public opinion by

suppressing news about Security Council countries than non-Security Council countries. Moreover,

we show that the closer the foreign country is aligned with the United States, the more severe the

distortion on news coverage. Our model implies that if there is government distortion, then we

should observe that the increase in news coverage that occurs with Council membership is declining

in magnitude with the level of alliance. For strongly allied countries, Council membership can

actually reduce the amount of news coverage.

The final and most important step in our paper is to estimate the differential relationship between

Council membership and U.S. news coverage for foreign countries of different levels of alliance with

the United States during the Cold War. We follow an earlier paper, Qian and Yanagizawa-Drott

(2009) and proxy for alliance with the degree to which a country votes with the United States in the

UN General Assembly on issues for which the United States votes in opposition to the Soviet Union

during the end of the Cold War.

5

Data on news coverage is collected from the text-analysis of five

large U.S. newspapers (New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune

and Los Angeles Times).

We examine the interaction effect of a time-invariant measure of Cold War alliance with the

U.S. and a time-varying measure of Council membership, while controlling for year and country

fixed effects. Country fixed effects control for all time-invariant characteristics across countries

such as cultural affinity with the United States, which can affect the degree of alliance, Council

membership and/or news coverage. Year fixed effects control for all changes over time that influence

5

Qian and Yanagizawa-Drott (2009) studies the relationship between political alliance with the United States and

human rights abuses reported by the U.S. State Department and Amnesty International. This earlier work does not

examine media news coverage or the United Nations Security Council.

3

all countries equally. The coefficient of the interaction term reveals the degree to which Council

membership differentially influences the news coverage of countries with higher levels of alliance and

the coefficient of the uninteracted Council membership term reveals the effect of Council membership

for the least allied countries with the United States in our sample. In the context of our framework,

finding a negative interaction would be consistent with the presence of government distortion, and a

positive coefficient for the uninteracted Council membership variable would be consistent with the

presence of the demand effect. These two forces are not mutually exclusive.

The results indicate that news coverage of human rights abuses of foreign countries during

the Cold War was influenced by both government distortion and reader demand. Taken literally,

our estimates imply that Council membership for a country that is on the 75th percentile of the

distribution of U.S. alliance (e.g., Ecuador, Egypt) will result in approximately 40% fewer news

articles about human rights abuses than Council membership for a country that is on the 25th

percentile of the distribution of alliance (e.g., Mali, the Republic of Congo).

Our results are consistent with U.S. news coverage being partly determined by government

distortions and partly driven by reader demand. This interpretation relies on the assumption

that there were no other forces that were simultaneously correlated with news coverage, Council

membership and political alliance with the United States. We do not take this as given and provide

a large body of evidence in support of our interpretation. For example, we show that the timing of

our reduced form effects corresponds with entry onto and exit from the Council. We also show that

our estimates are robust to controlling for a large number of potentially confounding factors such

as the interactions of the full vector of year fixed effects with variables such as Council membership

and U.S. alliance. See the section 6 for a detailed discussion.

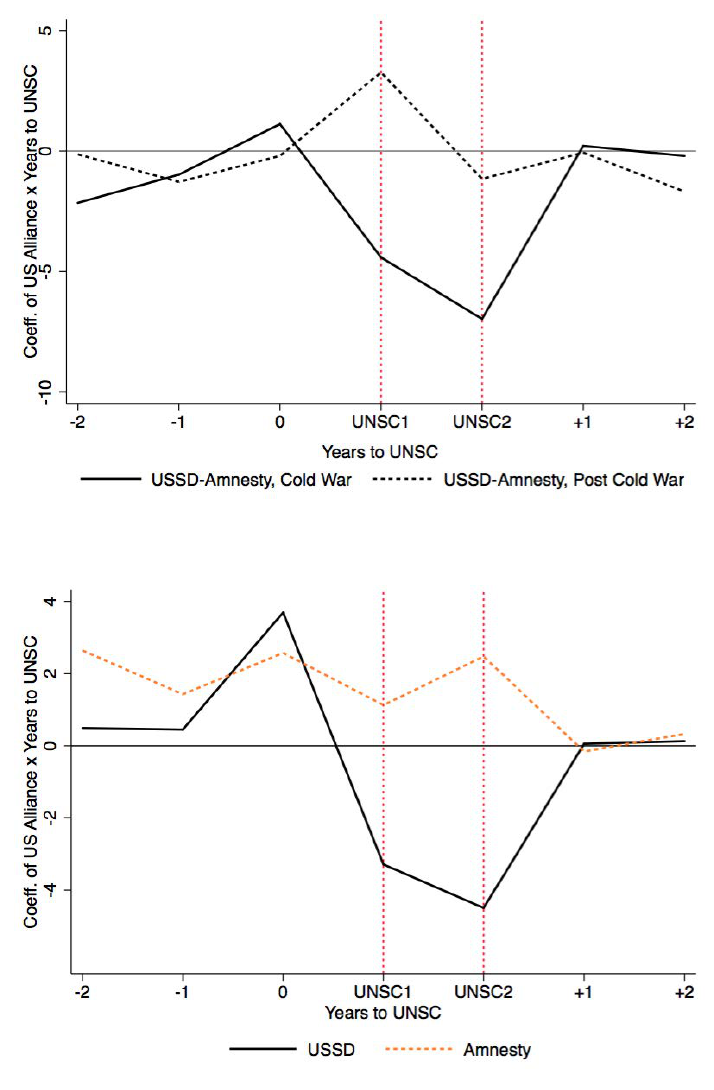

In addition, we provide several pieces of evidence to support our interpretation of the main

results. First, we show that the response of annual U.S. State Department reports of human

rights abuses of foreign countries to the interaction of alliance with the U.S. government and UNSC

membership is very similar to that of news coverage, which is consistent with our interpretation that

the interaction effect captures the influence of U.S. government manipulation. In contrast, reports

from Amnesty International, a non-government organization, do not respond to the interaction of

UNSC and U.S. alliance. This goes against the alternative explanation that our results reflect

changes in actual human rights practice. Second, we show that the interaction term of U.S. alliance

4

and UNSC membership has no effect on a large number of institutional measures that may be

correlated with human rights practices. This again goes against the alternative explanation that

the results on news coverage and U.S. State Department reports are driven by changes in actual

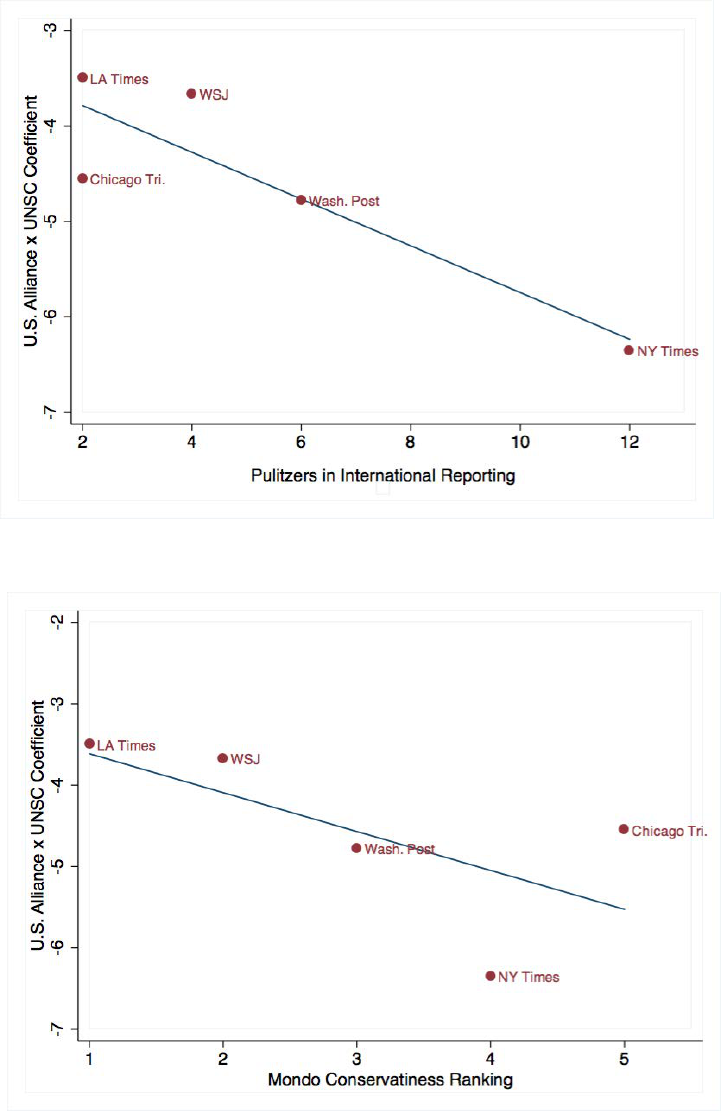

human rights behavior. Fourth, when we estimate the interaction effect for each newspaper, we find

that there is no correlation between the degree of distortion and reader preferences across papers.

While this should be interpreted very cautiously because there are only five newspapers, the results

are consistent with our interpretation that the interaction effects do not capture reader preferences.

In contrast, we find that the magnitude of distortion is positively correlated with newspaper quality

and reputation, which is straightforward to reconcile with our framework and that of Besley and

Prat (2006). Finally, we show that Council membership has no effect on news coverage after the

Cold War for any country. Amongst other explanations, this is consistent with the belief that the

U.S. government’s motivation for manipulating news of Cold War allies declined with the end of

the Cold War.

For policymakers, our results confirm the case evidence that systematic government-driven dis-

tortions can exist for independently owned and highly competitive media outlets in a democratic

regime. At the same time, one may view the fact that our effects dissipate with the end of the Cold

War as reassuring – i.e., it may be difficult for systematic manipulation to last indefinitely in such

contexts. We speculate on this more in the conclusion.

In our focus on the government’s influence of media coverage, our study is most closely related

to Besley and Prat (2006). It also builds directly on the pioneering work of Besley and Prat (2006),

Durante and Knight (2012), Prat and Stromberg (2005, 2011) and Stromberg (1999, 2004a, 2004b)

by adapting the frameworks developed in these papers and applying them to a novel empirical

context. To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first to provide rigorous evidence that

government distortion has systematically existed in the United States. In doing so, we add to

the important empirical literature on the determinants of news coverage. Our study differs from

previous studies in focusing on government-driven distortions in a democratic regime. In this sense,

we are related to two recent studies about the effect of partisan-controlled media in Italy under

Berlusconi (Durante and Knight, 2012) and the United States during 1869-1928 (Gentzkow, Petek,

Shapiro, and Sinkinson, 2012). The former study finds evidence of government influence on the

media in the modern Italian context, while the latter study finds that the government in power has

5

little influence over news composition in the historical U.S. context.

Second, we add to the small but growing number of political economy studies that explore the

causes and consequences of U.S. government foreign policy. In our focus on the Cold War era, our

study is most closely related to Dube, Kaplan, and Naidu’s (2011) study of U.S. covert actions on

U.S. firm stock prices, and Berger, Easterly, and Satyanath’s (2009) and Berger, Easterly, Nunn,

and Satyanath’s (2010) studies of U.S. Cold War policies on trade. It broadens the scope of this

literature by examining the effect of U.S. foreign policy on the American public. Finally, our use of

United Nations Security Council membership as a proxy for a country’s importance to the United

States borrow’s from Kuziemko and Werker’s (2006) insight that Council membership plays an

important role in the behavior of the U.S. government. Similarly, our use of voting in the UN

General Assembly as a proxy of U.S. alliance follows Alesina and Dollar (2000), which find that

voting with the U.S. in the General Assembly is positively correlated with U.S. foreign aid receipts.

6

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the background. Section 3 presents the

conceptual framework. Section 4 presents the empirical strategy. Section 5 describes the data.

Section 6 presents the main empirical results. Section 7 presents additional, more speculative,

results. Section 8 offers concluding remarks.

2 Background

2.1 “White Propaganda” During the Cold War

The main period of our study, 1976-1988, was characterized by a commitment to fight commu-

nism on the part of the American government, which climaxed during the Reagan administration

(1980-88). As with all of the Cold War, rivalry between the two superpowers was expressed through

military coalitions, propaganda and proxy wars (e.g., the Soviet war in Afghanistan 1979-89). The

Cold War ended during 1989-91 when the Berlin Wall fell and the U.S.S.R. dissolved. For the pur-

poses of our paper, we loosely interpret 1989 as the end of the Cold War. At this time, the strenuous

competition between the United States and the U.S.S.R. for the alliance of smaller countries ended.

An important feature of the Cold War in the United States was the focus on the superior

morality of the West. The U.S. government and news media often described its allies as “good”

6

Kuziemko and Werker (2006) finds that Council membership in years that are strategically important for the

U.S. government results in higher U.S. aid. They cleverly measure importance with the number of articles in the

New York Times about the Security Council.

6

and the Eastern Bloc and its allies as “evil”. Recently declassified files stored in the U.S. National

Security Archives document both the method and the motives for the U.S. government to influence

the press coverage of the human rights practices of its political allies.

The government needed public support for its political actions, which included public approval

of its political allies. Given the focus on morality, it followed that U.S. allies should have better

human rights abuses than Eastern Bloc allies.

7

For the most part, U.S. government support for its

Cold War allies with poor human rights abuses ended with the Cold War. Internal memos show

that the executive branch believed that one of the ways to shape public opinion against opponents

was to exaggerate human rights abuses in those countries and emphasize that amongst other things,

they were “evil”, “forced conscription” or engaged in the “persecution of the church”. Conversely,

the government attempted to increase support for political allies by calling them “freedom fighters”,

“religious” or simply “good” (Jacobwitz, 1985b).

The task of influencing press coverage was officially delegated to the Office of Public Diplomacy

(OPD) during the Reagan administration. The OPD was part of the State Department and worked

closely with the National Security Council (NSC). Its explicit purpose was to influence public and

congressional opinion to garner support for the President’s strong anti-communist agenda in a

“public action” program (Parry and Kornblub, 1988). The memo specifies that audiences for the

information campaign include the U.S. media (Jacobwitz, 1985b).

“..we can and must go over the heads of our Marxist opponents directly to the Amer-

ican people. Our targets would be within the United States... the general public [and]

media.” – Kate Semerad, an external relationship official at the Agency for International

Development (AID) in 1983.

Government methods for influencing the media can be broadly categorized into two groups. First,

the government can attempt to directly manipulate news reports by exerting pressure on editorial

boards or incentivizing journalists. The OPD monitored news reports by the American media and

would directly confront journalists and editors in order to convince them to change the reports

7

For studies on U.S. government favoritism of human rights reports of its Cold War allies, see studies such as

Carleton and Stohl (1985), Mitchell and McCormick (1988), Poe and Vazquez (2001), and Qian and Yanagizawa-

Drott (2009).

In the case of the The New York Times, which published an international version under the title of The International

Herald Tribune, manipulation could also affect the opinion of foreign readers. Also, influencing the press could also

affect congressional opinion, whose favor was often necessary for legislative purposes (Blanton and Blanton, 2007).

7

(Schultz, 2001). Upon the appearance of news reports that did not conform to the wishes of the

OPD, officials could press the owners and editorial boards to change their journalists in the field. The

OPD also dealt directly with journalists using a carrot-and-stick strategy. For example, uncoopera-

tive journalists became the targets of character assassination meant to induce skepticism about the

information they reported and were sometimes even forcibly removed from foreign countries from

which they were reporting.

8

In contrast, journalists seen as cooperative to the administration’s

agenda were rewarded with increased access to government information. For example, an OPD

memo stated that certain favorable correspondents had “open invitations for personal briefings”

(Cohen, 2001).

9

Second, the government can manipulate the supply of information and provide disinformation.

Information can be disseminated through the numerous government affiliated publicity events and

publications. One such publication is the Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, which we will

discuss later in the paper. In a letter to House Speaker Patrick Buchanan, the Deputy Director for

Public Diplomacy for Latin American and the Caribbean (SLDP), Jonathan Miller, described how

the OPD was carrying out “white propaganda” operations. This included writing opinion articles

under false names and placing them in leading newspapers such as the Wall Street Journal (Hamilton

and Inouye, 1987; Miller, 2001). Similar opinion editorials were planted in the New York Times

and the Washington Post (Brooks, 1987). The OPD paid extra attention to prominent journalists.

In general, the OPD flooded the media, academic institutions and other interested groups with

information. For example, in 1982, the OPD booked more than 1,500 speaking engagements with

editorial boards, radio, and television interviewers, distributed materials to 1,600 college libraries,

520 political science faculties, 122 editorial writers, and 107 religious groups (Parry and Kornblub,

1988).

2.2 The United Nations

The United Nations (UN), a source of much of the diplomatic influence and the principal outlet

for the foreign relations initiatives of non-superpower countries, was especially important during the

8

One famous case was the removal of New York Times reporter Raymond Bonner from El Salvador after his

unfavorable reporting of the massacre by the Salvadoran government. The U.S government pressured the NYT to

recall Bonner (Parry and Kornblub, 1988). Other outlets such as the Wall Street Journal subsequently published

articles criticizing the NYT for publishing Bonner’s reports.

9

Blanton and Blanton (2007) provides an overview of all the actions taken by the Office for Public Diplomacy

(OPD) during the Reagan Administration (1980-88). For detailed accounts of when the media allows the government

to distort reports, see Bennet, Bennet and Livingston (2007) and Thomas (2006).

8

Cold War.

10

Two of the five principal organs of the UN are the General Assembly and the Security

Council (UNSC). During the period of our study, there were approximately 150 member countries,

of which more than two-thirds were developing countries. The General Assembly votes on many

resolutions brought forth by sponsoring states. Most resolutions, while symbolic of the sense of the

international community, are not enforceable as a legal or practical matter. The General Assembly

does, however, have authority to make final decisions in areas such as the UN budget, and in case

of a split vote in the Council when no veto is exercised, the issue goes for a vote in the General

Assembly.

The Security Council is comprised of fifteen member states. Hence, it is significantly smaller

than the General Assembly. Council members have more power than General Assembly members

because the Council can make decisions which are binding for all UN member states, including

economic sanctions and the use of armed force (Chapter Seven of the UN Charter). There are

ten temporary seats that are held for two-year terms, each one beginning on January 1st. Five

are replaced each year. The members are elected by regional groups and confirmed by the UN

General Assembly. New members are typically announced the year before the term begins.

11

There

are five permanent members (P5): China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United

States. These members hold veto power for blocking adoption of a resolution. Experts vary in their

assessment of the power of rotating members over important issues during our period of study. On

the one hand, rotating members cannot overturn vetoes and some political scientists argue that

they have limited real power (e.g., O’Neill, 1996). On the other hand, studies such as Voeten (2001)

argue that P5 countries prefer multilateral agreements, which, in turn, gives much power to rotating

members. For example, deadlocks on the Council can only occur if there is no veto and nine of the

ten deadlocks that have ever occurred in the history of the UN occurred during the Cold War.

12

10

For a detailed discussion of the history and institutions of the United Nations, see Malone (2004).

11

Africa elects three members; Latin America and the Caribbean, Asian, and Western European and others blocs

choose two members each; and the Eastern European bloc chooses one member. Also, one of these members is an

Arab country, alternately from the Asian or African bloc. Members cannot serve consecutive terms, but are not

limited in the number of terms they can serve in total. There is often intense competition for these seats (Malone,

2000).

12

1956 Suez Crisis; 1956 Soviet Invasion of Hungary (Hungarian Revolution); 1958 Lebanon Crisis; 1960 Congo

Crisis; 1967 Six Days War; 1980 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan; 1980 Israeli-Palestinian Conflict; 1981 South African

occupation of Namibia (South West Africa); 1982 Israeli Occupation of the Golan Heights (Golan Heights Law); 1997

Israeli-Palestinian conflict (East Jerusalem and Israeli-occupied territories).

9

3 Model

In this section, we develop a framework of how alliance with the U.S. government and member-

ship on the United Nations Security Council can interact to affect U.S. news coverage of human

rights abuses of foreign countries. Specifically, our framework studies the incentives of the govern-

ment to distort media coverage of state repression in foreign countries. In our model, domestic

voters care in part about the foreign policy that the U.S. government pursues, but voters cannot

directly and fully evaluate the foreign policy (preferences) of the incumbent. Voters partly base

their inferences on the behavior of allied foreign countries that vote with the United States in the

UN. News reports about human rights violations of the allies serve as indicators of U.S. foreign

policy, which affects the probability that the incumbent U.S. government will be voted out of the

office.

Before presenting the formal model, we sketch the basic intuition behind it. In our model, “worse”

countries are more likely to commit human rights violations and are more likely to vote with the

United States if the U.S. government’s foreign policy is bad. U.S. voters observe voting behavior

and read about human rights violations to make their inferences about the U.S. government’s type.

There are two groups of voters. The first group is interested in and reads the news about all

foreign countries. As a result, voters in the first group make inferences based on the behavior of

all countries. The second group is interested only in the countries that are currently on the UNSC.

We do not formally model the reason for this. This assumption is motivated by the fact that the

Council discusses more important issues and/or has more power over these issues. Alternatively,

it could simply be because being on the Security Council acts as a focal point for readers with

limited interest in foreign policy. The second group solely bases its inferences on the news coverage

of Council members.

In our model, obtaining a seat on the Security Council generates two effects on news coverage.

The first is a demand effect. As a country becomes a member of the Council, more people are

interested in reading about it. In the absence of government interference, newspapers would then

increase their coverage of human rights abuses in these countries. The second effect is a distortion

effect that comes from the incentives of the government to manipulate the media. We show that if the

number of countries not on the Council is much larger than the number of countries on the Council

10

(e.g., the General Assembly), it is much cheaper for the U.S. government to manipulate public

opinion by suppressing news about Security Council countries than non-Security Council countries.

Because voters in the first group based their inferences on voting and human right violations of all

countries, distorting news coverage about one of them has little effect on the posterior beliefs of this

group when the total number of countries is large. In contrast, the voters in the second group base

their inferences on the voting behavior of a relatively small number of countries on the Council, and

the distortions in the coverage of one country has a large effect on the voters’ posterior beliefs about

the U.S. government’s type. As a result, when the country enters the Council, it is optimal for the

U.S. government to significantly intensify its distortion of news coverage. Moreover, this effect is

monotone. The closer the foreign country is aligned with the United States, the more severe the

distortion will be.

Methodologically, our approach combines recent theories of endogenous news coverage developed

by Prat and Stromberg (2005, 2011) and Stromberg (1999, 2004a, 2004b) with a theory of media

manipulation by Besley and Prat (2006). That voters in our model try to infer the quality of the

government policies from news reports and that newspaper coverage affects the posterior beliefs of

the voters about the quality of those policies is very similar to Durante and Knight (2012).

13

The

ultimate goal of our model is to derive testable implications to guide the empirical investigation of

whether there is government distortion in the context that we study.

3.1 Setup

Our model of media coverage is a close adaptation of Prat and Stromberg (2011, section 5), and

we mostly follow their notation. We consider a simple two-period model with no discounting. An

incumbent U.S. government has type θ

US

, which is the same in both periods. In the end of period

one, U.S. voters decide whether to keep the incumbent or replace it with a challenger. Both the

incumbent’s and the challenger’s types are drawn from a uniform distribution which takes values

on [0, 1] . Neither type is observed directly by voters. Voters make inferences about the incumbent’s

type from the U.S. government’s voting record in the UN General Assembly and from news coverage

of U.S. allies in the UN. Higher θ

US

corresponds to the U.S. government being “better” from the

point of the of domestic voters.

13

Durante and Knight (2012) studies the optimal choice of news outlet based on their ideological leaning. We

abstract from the differences in ideology and focus on the incentives of the government to manipulate news coverage.

11

There are four main groups of players in our model: the U.S. government, foreign governments,

U.S. voters and the U.S. media. We discuss each of these groups in turn.

3.1.1 U.S. government

The U.S. government cares about two objectives: i) passing the foreign policy issue that it favors

in the UN, and ii) rents associated with being in office. It has two instruments at its disposal to

achieve its goals. The first instrument is its vote on a given issue. The second is the distortion

of newspapers to get favorable coverage. We assume that the U.S. government votes sincerely and

focuses on the incentives to distort the news coverage.

14

3.1.2 Foreign governments

We assume that there are N + 1 foreign countries and each country n can be one of the two

types, either “bad” (θ

n

= 0) or “good” (θ

n

= 1). For concreteness, we assume that each country’s

type is drawn ex-ante independently and is equally likely to take either type. In the UN, the U.S.

and foreign countries vote on a large number of resolutions. Each issue, x

j

, takes a value which is

being drawn from a uniform distribution on [0, 1] . The payoff for a country of type k ∈ {0, 1, US}

if the resolution j is passed is

1

4

− (x

j

− θ

k

)

2

. (1)

The payoff if a resolution is not passed is normalized to zero.

Under the assumption that countries vote sincerely, this convenient formalization means that

the U.S. votes with a country of type θ

k

= 0 with probability 1 − θ

US

and with a country of

type θ

k

= 1 with probability θ

US

. Since we assume that the number of resolutions is large, the

observed frequency of voting with country k reveals the degree of alliance with the United States,

A

US,k

= |θ

US

− θ

k

|, perfectly.

Out of N + 1 foreign countries, one is randomly selected to be on the Council. Without any

loss of generality, we denote this country by n = N + 1. In this model, the only distinction between

being and not being on the Council is that more U.S. voters will be interested in reading the news

about countries on the Council.

15

14

It is possible to extend this model to account for strategic voting by the U.S. and show that the main insights

continue to hold in that case. This extension is available upon request.

15

One can make the case that, in general, more information will be revealed about a country’s type when it is on the

Security Council, for example, because policy deliberations generally reflect more important issues. Such mechanisms

will generally strengthen the effect we consider in this model.

12

Foreign governments of type θ

n

= 0 are repressive and commit human rights abuses. Govern-

ments of type θ

n

= 1 are not repressive and do not abuse human rights.

3.1.3 U.S. Voters

U.S. voters do not observe foreign governments’ types or the U.S. government’s type directly.

Voters read newspapers and they become informed about the type of the foreign government and

how closely it is allied with the United States with some probability. We assume that there are two

groups of voters. Group 1 reads news about all foreign countries. Group 2 reads only about foreign

countries that are “powerful”, i.e., on the UN Security Council.

16

Let m

1

and m

2

be the strictly

positive fraction of voters in groups 1 and 2, respectively.

In the next section, we describe how voters become informed. Based on media coverage, some

fraction s of the population becomes informed about human rights violations of foreign governments

and how frequently that government voted with the United States. Both pieces of information,

therefore, perfectly reveal the type of the incumbent, θ

US

. A fraction, 1 − s, remains uninformed,

and their posterior beliefs about the incumbent type remains unchanged, with the expected value

of 1/2.

The expected utility from keeping the incumbent in office in period 2 is E [θ

US

], where E is the

expectation given the information that each voter has. The utility from selecting the challenger is

E [θ

0

US

] + δ, where E [θ

0

US

] is the expected challenger’s type and δ is an idiosyncratic characteristic

of the challenger. We assume that δ is uniformly distributed on [−1/2, 1/2] .

For brevity, we focus on sincere voting. Since θ

0

US

is drawn from the same distribution as θ

US

,

the uninformed voters vote for the incumbent if −δ ≥ 0, which occurs with probability 1/2. The

informed agents vote for the U.S. government if θ

US

− 1/2 − δ ≥ 0. The δ to satisfy this condition

is realized with probability θ

US

. Therefore, the probability of re-election of the incumbent, µ, is

µ = sθ

US

+ (1 − s)

1

2

. (2)

We study how voters become informed in the following section.

16

As in Prat and Stromberg (2011), one can allow for an arbitrary number of groups and issues that are policy-

relevant. We focus on foreign news given the nature of the data in the empirical section, but the main implications

of the model are potentially applicable to domestic news as well.

13

3.1.4 Mass Media

We now consider the media market. The main idea is that bigger news coverage about any

country increases the fraction of voters informed about it. We follow the arguments of Prat and

Stromberg (2005, 2011) and Stromberg (1999, 2004a, 2004b) . Let q

n

be the amount of news coverage

for country n. A reader buys the newspaper based on the amount of coverage and on idiosyncratic

characteristics. The reader knows that if he buys a newspaper with q

n

stories about country n,

he will find the news to be entertaining and the information to be relevant with probability ρ (q

n

),

where ρ is an increasing function. If the reader finds the information entertaining, he obtains 1 unit

of utility. Let ε

i

be the reader’s exogenous idiosyncratic valuation of newspapers, which is uniformly

distributed on [0, 1] . If the price of the newspaper is p, the reader buys it if

ρ(q

n

) − ε

i

≥ p.

For simplicity, we assume that ρ (q) = q and the parameters of the model are such that in equilib-

rium, q ≤ 1. Thus, if the newspaper has q

n

news about country n, the probability that a reader is

interested in country n is max {q − p, 0} . Once a reader buys the newspaper, he learns that θ

n

= 1

and the degree of alliance of that country with the United States, A

US,n

, which is sufficient for

inferring the true type of the U.S. government, θ

US

.

As in Prat and Stromberg (2005, 2011), we assume that newspapers operate an increasing

returns to scale technology, since there are costs of gathering news and writing a story which is

independent of the number of newspaper copies sold. We assume that news cannot be fabricated,

and it is therefore impossible to write about human rights violations for countries for which θ

n

= 1.

For countries that commit human right violations (θ

n

= 0), newspapers select the optimal amount

of coverage. The cost of publishing q

n

stories is

γ

2

q

2

n

+ ˜m (q

n

− p) d,

where d reflect the cost of distribution, γ > 0 is a parameter, and ˜m = m

1

+m

2

for a country on the

Security Council and ˜m = m

1

for any other foreign country. Here, the first term is the fixed cost

that is independent of the number of copies and the second term represents constant marginal costs,

14

d, which are proportional to the demand for newspaper, ˜m (q

n

− p) . The profit for the newspaper

from publishing q

n

news is then

Π (q

n

) = (p − d) ˜m (q

n

− p) −

γ

2

q

2

n

. (3)

For simplicity, we assume that there is only one newspaper and that p is exogenous and greater

than d. Both of these assumptions can be relaxed along the lines suggested by Stromberg (2004a,

2004b).

Before we characterize the equilibrium with news manipulation, it will be informative to describe

the equilibrium when the government does not interfere. In this case, the optimal news coverage ˆq

n

maximizes (3) for each n for which θ

n

= 0. It is straightforward to see that ˆq

n

satisfies

ˆq

n

=

0 if θ

n

= 1

1

γ

(p − d) m

1

if θ

n

= 0 and n ≤ N

1

γ

(p − d) (m

1

+ m

2

) if θ

n

= 0 and n = N + 1

. (4)

This implies that news coverage of human rights abuses is higher if the country joins the Council.

To make sure that ˆq

n

−p are well defined probabilities when θ

n

= 0, we assume that (p, d, m

1

, m

2

, γ)

jointly satisfy

1

γ

(p − d) m

1

− p > 0,

1

γ

(p − d) (m

1

+ m

2

) < 1.

To find the probability with which the U.S. incumbent retains power, we need to find the number

of informed voters. We start with group 2. In the context of our model, if the country on the Security

Council does not commit any human rights violations, then no news coverage is available and all

voters in group 2 retain their prior beliefs that the probability that the U.S. government is of type

1 is 0.5.

17

If the country committed human rights violations, then fraction

1

γ

(p − d) (m

1

+ m

2

) − p

17

In principle, the lack of news about country n can be an informative signal about country n, since in our model,

all news is assumed to be bad news. For simplicity, we assume that readers update their beliefs about country n (and

about the U.S. government) only if they read the news about this country and if they find the news entertaining. In

a richer model in which good news can be generated about good countries, this issue does not arise and the analysis

of that model is very similar to the one presented in this section. Since our empirical strategy allows us to identify

15

of voters in group 2 will see the news and learn that the true type of the U.S. government is θ

US

.

The fraction 1 −

1

γ

(p − d) (m

1

+ m

2

) − p

remains uninformed and retain the prior that the U.S.

government is of type 1 with probability 0.5.

Next, we turn to voters in group 1. A voter learns the type of the U.S. government if she spots

news coverage for at least one country. Suppose that out of the N countries,

˜

N commit human

rights violations and the country on the security council is also type θ

N+1

= 0. Then the probability

that she does not spot any news coverage is and retains her prior belief is

(1 − max {ρ (ˆq

1

) − p, 0}) × ... × (1 − max {ρ (ˆq

N+1

) − p, 0})

=

1 −

1

γ

(p − d) m

1

− p

˜

N

1 −

1

γ

(p − d) (m

1

+ m

2

) − p

.

Then the total share of informed voters who learn the type of the U.S. government, s, is

s =

1 −

1 −

1

γ

(p − d) m

1

− p

˜

N

1 −

1

γ

(p − d) (m

1

+ m

2

) − p

!

m

1

+

1

γ

(p − d) (m

1

+ m

2

) − p

m

2

.

Note that this pins down the probability of the U.S. incumbent retaining power, as given by (2).

3.1.5 Equilibrium with manipulation

Next, we turn to describing the equilibrium with manipulation. We keep the basic structure of

the game the same as before. We introduce one more stage, following the logic of Besley and Prat

(2006), in which the U.S. government can offer a transfer T (∆

n

) to the newspaper and suppress

∆

n

news from publication.

18

The newspaper can either reject the transfer and publish its profit-

maximizing news quantity or accept it and publish at most q

n

. We keep the rest of the model as

above.

Let s

{q

n

}

N+1

n=1

be the fraction of voters who are informed if country n has q

n

reports of human

rights abuses. Suppose that R is the value of the incumbent to remain in power, which is strictly

only bad news, we focus on this simpler set up.

18

As in Besley and Prat (2006), the bribe that the U.S. government pays to a newspaper is not necessarily a

monetary transfer, but can be different forms of non-pecuniary benefits that affect newspaper profits, such as offering

exclusive interviews with the incumbent or leaking valuable political information to the newspaper.

16

positive. Then the incumbent solves

max

{q

n

}

N +1

n=1

s

{q

n

}

N+1

n=1

θ

US

+

1 − s

{q

n

}

N+1

n=1

1

2

R −

N+1

X

n=1

T (ˆq

n

− q

n

) (5)

subject to

T (ˆq

n

− q

n

) + Π (q

n

) ≥ Π (ˆq

n

) for all n

and

q

n

≤ ˆq

n

.

Here, the first constraint is a best response for the newspaper that agrees to suppress ∆

n

= ˆq

n

−q

n

news only if its profits from doing so exceed the profits from rejecting the offer. The second constraint

ensures that the newspaper cannot publish more news than the newspaper had originally planned

and, in particular, that no human rights violation stories can be fabricated for countries θ

n

= 1.

This problem is, in general, not well behaved. Function s is neither concave nor convex, which

makes the analysis harder. The problem simplifies when we focus on the empirically relevant case

when the number of countries is large. In this case, it is easy to show that it is (approximately)

not optimal to distort countries that are not on the Security Council. The reason for this is as

follows. Note that the probability that a voter in group 1 is not informed about the type of the

U.S. government is (1 − max {ρ (q

1

) − p, 0}) × ... × (1 − max {ρ (q

N+1

) − p, 0}) . When N is large,

so is the number of countries which violate human rights,

˜

N. If the probability that newspapers

report human rights violation for such countries is positive, max {ρ (q

n

) − p, 0} > 0, the fraction

of uninformed types in group 1 becomes very small. The only way to substantially change the

fraction of informed is to significantly suppress news for a large number of countries, which becomes

prohibitively costly for a large N.

Formally, let {q

∗

n

}

N+1

n=1

be the equilibrium quantities of news that are a solution to (5). We have

the following result, which we formally prove in the Appendix.

Lemma 1 Suppose N is large. Then q

∗

n

≈ ˆq

n

for n = 1, ..., N

Next, we focus on the distortion of news for a foreign country on the Council. Let s

1

{q

n

}

N+1

n=1

and s

2

(q

N+1

) be the fraction of informed citizens in groups 1 and 2. When q

∗

N+1

is interior, the

17

first order condition for q

∗

N+1

is

∂

∂q

N+1

s

1

{q

∗

n

}

N+1

n=1

+

∂

∂q

N+1

s

2

q

∗

N+1

θ

US

−

1

2

R + (p − d) (m

1

+ m

2

) = q

∗

N+1

.

For the reasons explained in the proof of Lemma 1, as N → ∞,

∂

∂q

N +1

s

1

{q

∗

n

}

N+1

n=1

→ 0

and therefore for large N , we can ignore this term. Since s

2

(q

N+1

) = m

2

(q

N+1

− p) , the above

expression becomes

q

∗

N+1

= (p − d) (m

1

+ m

2

) +

θ

US

−

1

2

Rm

2

.

Since q

∗

N+1

≤ ˆq

N+1

, this condition holds only for

θ

US

−

1

2

≤ 0. For

θ

US

−

1

2

> 0, the optimal

news suppression is zero, q

∗

N+1

− ˆq

N+1

= 0.

This result allows us to compare news coverage of a country on the Council and an identical

country not on the security council. If this country is of type 1, there is obviously no news coverage

of human rights violations in any case. If the country is of type 0, the difference in coverage ∆ is

given by

∆ = (p − d) m

2

| {z }

demand effect

− max

1

2

− θ

US

Rm

2

, 0

| {z }

distortion effect

.

This formula shows that news coverage is determined by two effects when a country gets on

the Security Council. The “demand effect” leads to an increase in coverage since more people want

to read about the country on the Security Council. The “distortion effect” leads to a decrease in

coverage for allies that violate human rights. Moreover, the closer the United States is allied to

the foreign country (i.e., the lower θ

US

), the stronger this effect will be. Since distortion occurs if

θ

US

≤

1

2

and the foreign country on the Security Council is of type 0, which happens with joint

probability 1/4, in expectation the distortion effect is positive. We summarize these findings in the

theorem

Theorem 2 For a repressive country not allied with the United States, news coverage of its human

rights violations increases when it enters the Security Council. The magnitude of the increase

declines with the degree of alliance. If the benefit of being in power, R, is sufficiently large, then

news coverage falls for close allies when they enter the Council.

The empirical analysis investigates whether these relationships are present in the data.

18

4 Empirical Strategy

The relationship between news coverage, U.S. alliance and Council membership can be charac-

terized as the following:

Y

it

= β(A

i

× C

it

) + αC

it

+ θX

it

+ γ

i

+ δ

t

+ ε

it

, (6)

where the outcome variable, news coverage of human rights abuses, in country i in year t, Y

it

,

is a function of: the interaction of alliance to the United States, A

i

, and membership on the

Security Council, C

it

; the uninteracted term for Council membership; a vector of country-year

specific controls, X

it

; year fixed effects, δ

t

; and country fixed effects, γ

i

. The standard errors are

clustered at the country level to adjust for serially correlated shocks within countries. The country

fixed effects control for all time-invariant differences across countries. Year fixed effects control for

changes over time that affect all countries similarly. X

it

includes a vector of country-year controls,

which will be motivated and discussed later as they become relevant. Note that our measure of

alliance is time-invariant and collinear with country fixed effects. Therefore, we do not control for

the uninteracted alliance term in the baseline regression.

Our strategy is conceptually similar to a differences-in-differences (DD) strategy. We compare

outcomes for countries when they are on the Council to when they are not, between countries that

are strongly allied to the United States to those that are less allied. α is the association of Council

membership and news coverage for foreign countries that are not allied to the United States at all,

A

i

= 0. β is the differential association of Council membership and news coverage between countries

that are not allied at all, A

i

= 0, and countries that are “perfectly” allied, A

i

= 1. α + β is the

“net” or “total” association between news coverage and Council membership for countries that are

perfectly allied with the United States. In the context of our conceptual framework, finding

ˆ

β < 0

will be consistent with the presence of government distortion (i.e., the news is partly determined by

U.S. government distortion), and that ˆα > 1 will be consistent with the presence of reader demand

effects (i.e., the news is partly determined by reader demand). These two effects are not mutually

exclusive and can co-exist. Finding that ˆα + A

ˆ

β < 0 means that for a country that is allied with

the United States by A or more, Council membership will reduce news coverage.

19

Interpreting the association between the interaction effect and news coverage as causal requires

the assumption that Council membership does not differentially affect allies in some way that will

influence news coverage through channels other than U.S. government distortion or reader demand.

Specifically, for the interaction term to overstate the true degree of government distortion, the

omitted factor needs to reduce the increase in news coverage according to the level of political

alliance with the United States. For example, if improvement in human rights practices when

entering the Council is positively correlated with alliance, then the interpretation of our estimates

will be confounded. We will carefully consider this and other robustness concerns after we present

the main results.

5 Data

This paper uses data that are constructed from numerous publicly available sources. For brevity,

we only describe the data for the main analysis in this section. Other data will be discussed as they

become relevant.

News coverage of human rights violations is measured as the number of newspaper articles about

human rights abuse in a given country. Following the definitions used by Freedom House and the

Political Terror Scale project, we define human rights as physical violence committed by the state

onto civilians. We calculate the number of articles based on a search of the text of articles in

the ProQuest Historical and National Newspapers database. We search for articles containing the

country’s name, the phrase “human rights” and require at least one of the words or phrases that

fall under the UN Declaration for Human Rights (and that are therefore also commonly used in

news articles on human rights abuse). These include “torture”, “violations”, “abuse”, “extrajudicial”,

“execution”, “arbitrary arrests”, “imprisonment” and “disappearances”. Our measure of human rights

coverage is the total number of articles that results from the search per country per year. The

newspapers we examine are The New York Times (NYT), The Washington Post, The Wall Street

Journal (WSJ, only available 1976-91), The Chicago Tribune (only available 1976-86) and The Los

Angeles Times (L.A. Times).

19

These are the only newspapers with high circulation for which we

could conduct a full text search for the main period of our study. All of the newspapers in our

19

In an earlier version of the paper, we also used news from the Christian Science Monitor. Since we want to focus

in newspapers with large circulation, we have dropped this much smaller newspaper from the sample. All of the

results are similar with its inclusion. Please see the earlier version for those results.

20

sample are in the top ten of the highest circulation newspapers in the United States. Our measure

includes both articles written by journalists employed by newspapers and stories picked up from

newswires and other sources, although the newspapers in our sample, and in particular the NYT

and Washington Post, were known for original international news reporting.

20

This does not affect

the interpretation of the results, but for completeness, we will also examine the impact on articles

from newswires after we present the main results.

We proxy for the degree of alliance with the United States during the Cold War using the mean

fraction of votes that a country votes in agreement with the United States on issues for which

the United States votes in opposition to the Soviet Union in the UN General Assembly, A

i

, where

A

i

∈ [0, 1].

21

Our measure of alliance includes abstentions.

22

Our main measure of alliance is the

fraction of votes a country voted with the United States averaged over the period 1985-88. This

period provides us with the highest number of divided votes and therefore the best measure of

alliance during this period. We use a time-invariant measure of alliance because it is less likely to

be an outcome of changing U.S. favoritism than a time-varying measure and because using voting

patterns from years where there were very few divided issues produces a very noisy measure of

alliance.

23

Data on Council membership are collected from The United Nations Security Council Member-

ship Roster.

24

This is a time-varying dummy variable for whether a country is a rotating member

20

The source of the story is often embedded within an article. Therefore, we were not able to accurately and

systematically distinguish between articles written by different sources.

21

Each year, there are approximately 100-150 resolutions in the Assembly, of which the United States and U.S.S.R.

disagree on approximately 70-90. We do not examine voting patterns in the Council because most issues are discussed

prior to being put onto the agenda. Therefore, the sample of issues voted on are not representative of the actual

issues being deliberated by Council members.

22

Excluding them does not significantly change either the measure of alliance or the regression results. For brevity,

we do not report those results in the paper.

23

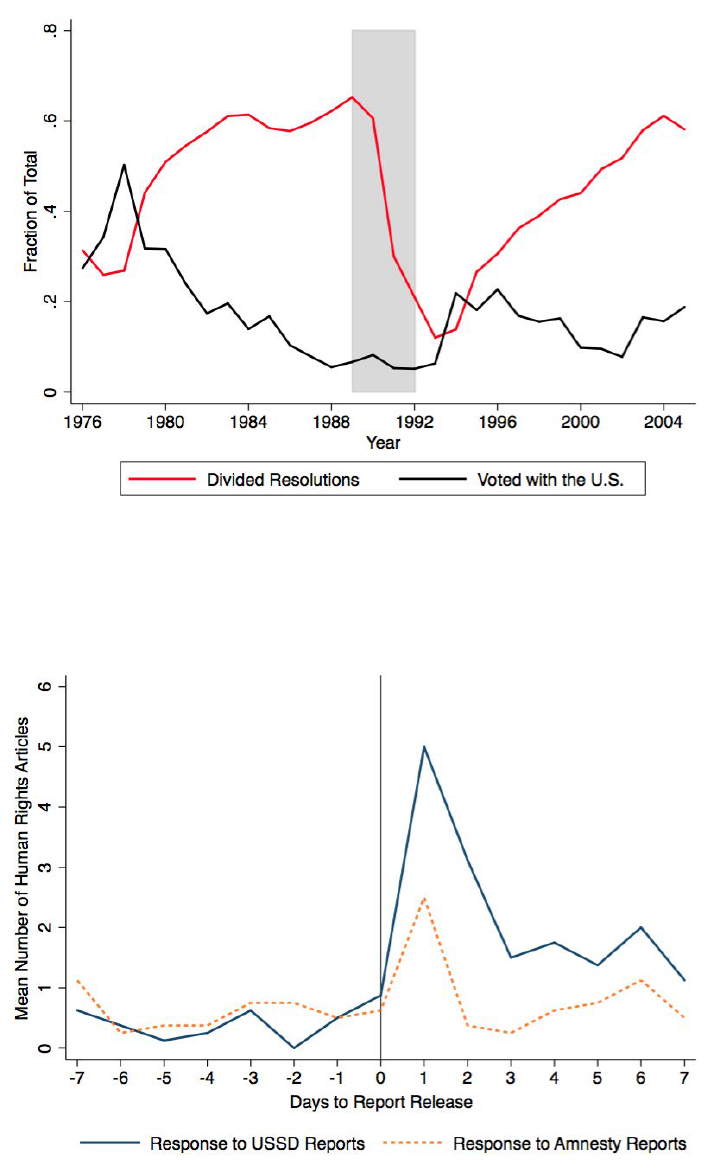

Figure A.1 plots the fraction of divided votes over time. It shows that as Cold War tensions escalated in the

1980s, the fraction of divided votes increased from approximately 30% during the late 1970s to almost 70% in the late

1980s. Also plotted are the fraction of votes with the United States averaged over all the divided votes each year.

Using the measure of alliance presented in the paper, the top three allies of the United States and the fraction of

divided issues they voted with the United States are: Turkey (0.4), Belize (0.28) and Costa Rica (0.27). The three

countries that are least allied are Mongolia (0), Lao PDR (0), and Czech Republic (0). Our estimates are robust to

changing the measure of alliance to be the average of votes during periods between 1981 and 1989, when there were

many divided votes. The magnitude of the estimates vary slightly across different definitions, but the results are

always qualitatively similar. For brevity, we do not report estimates with these alternative measures in the paper.

They are available upon request.

24

See http://www.un.org/sc/list_eng5.asp for a list of all countries that were ever members and the years of their

memberships. 46 countries in the sample were on the Council as a rotating member at least once during this time.

They are listed in Appendix Table A.1. 21 countries were on the Council at least twice, among which five countries

were on the Council three times.

21

of the UN Security Council, C

it

.

We will also use reports on human rights practices in our analysis. These indices are provided

by the Political Terror Scale (PTS) project for the years 1976-2005 and measure the annual extent

of human rights violations according to two sources: the U.S. Department of State (USSD) Country

Reports on Human Rights Practices, and the Amnesty International Annual Report. The PTS uses

a five point coding scheme, where a PTS value of five indicates the most severe abuse, and a PTS

value of one means that the country is under a secure rule of law and people are not imprisoned for

their views. The scale is based on an earlier one developed by Freedom House. As we are interested

in countries that commit human rights violations, we restrict our analysis to countries that have an

Amnesty International PTS value above one in at least one year.

25

The final sample of countries excludes former Soviet Republics that did not have membership

in the United Nations before 1991 and South Africa, which was excluded from UN activities due to

the UN’s opposition to apartheid. The five permanent members of the Council are also excluded

since they cannot experience any variation in Council membership.

The main analysis focuses on the Cold War years, 1976-88. The sample begins in 1976 because

of the limitation of the PTS data. The sample ends in 1988, the year prior to the fall of the Berlin

Wall, which we interpret as the “beginning of the end” of the Cold War era. Our estimates are

qualitatively similar if we include 1989-1991.

26

The main sample comprises of an unbalanced panel

of 91 countries. The panel is unbalanced due to the fact that the number of countries in the United

Nations increases over time. After we present the main results, we will show that our estimates are

not driven by selection of countries into the United Nations, and we will also show the results from

using data from the post-Cold War period.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics. Panel A shows the Cold War period. Panel B shows

the post-Cold War period. We focus our discussion on the former. The data show that the average

country in our sample votes with the United States on 8.9% of divided issues. Approximately 7% of

the country-year observations are Security Council members. The sample average for human rights

25

A PTS value of two implies (among other things) there is “a limited amount of imprisonment for nonviolent

political activity... A few persons are affected; torture and beating are exceptional... and political murder is rare.”

The CIRI Human Rights Data Project, like the PTS Project, reads the reports by Amnesty and the State Department

and provides a score. However, the CIRI indices only begin in 1981. They also differ from PTS in that they attempt

to provide disaggregated indices for the type of human rights. This means that while the two indices are correlated

(approximately 0.65-0.73), they are not directly comparable. See Wood and Gibney (2010) for a detailed discussion.

26

These results are available upon request.

22

practices is “medium” since the PTS index ranges from one to five and the mean PTS in the sample

is close to three. The U.S. State Department reports countries as having better human rights, on

average, than does Amnesty International.

The statistics also show that approximately 60% of the country-year observations have at least

one news article published on human rights in a U.S. newspaper. The U.S. newspapers in our sample

published almost eight articles about the human rights abuses of the average foreign country in our

sample each year. The Washington Post, New York Times and Los Angeles Times published three

to ten times as many articles as the Wall Street Journal or the Chicago Tribune. We will discuss

newswire and U.K. newspapers later in the paper.

6 Results

6.1 Main Results

In this section, we present the estimates of equation (6). Table 2 presents our main results on

news coverage. The sample means of the dependent variables are presented at the top of the table.

Our main measure of news coverage is the log of the number of news articles about country i’s

human rights abuses during year t across all newspapers.

27

In panel A column (1), we control for

the uninteracted U.S. alliance term instead of country fixed effects to examine the coefficient for this

variable. When we do this, the interaction effect is negative, but statistically insignificant. The main

effect of Council membership is positive, but statistically insignificant. The main effect of alliance

is positive and almost significant at the 10% level, which implies that alliance and news coverage

is positively correlated for countries not on the Council. However, this should be interpreted very

cautiously as only suggestive because U.S. alliance is almost certainly endogenous to a large number

of other factors.

28

Column (2) replaces the control for U.S. alliance with year fixed effects. This greatly increases

the precision of the estimates for the interaction effect and the uninteracted Council effect without

causing much change to the magnitudes of the estimates. The interaction effect is statistically

significant at the 10% level and the uninteracted Council effect is significant at the 1% level. In

27

If there are zero articles, we calculate this as the log of 0.1 to maximize sample size. To check that our results

do not rely on this transformation, we will later show the estimates for the number of articles (without taking logs)

and the log number of articles on a sample restricted to observations where there is at least one article.

28

Note that our model, which assumes that readers do not distinguish allies from non-allies, is silent on the

relationship between alliance and news coverage for non-Council members.

23

column (3), we replace the control for the uninteracted Council effect with the interaction of the

Council dummy with the full vector of year fixed effects to address the possibility that the importance

of Council members to the U.S. government or the prominence of the Council to the American public

changes over time. Adding this control increase the precision of the interaction effect to the 1%

significance level.

In column (4), we additionally control for the interaction of U.S. alliance and the full vector of

year fixed effects to address the possibility that the relationship between the U.S. government and

its allies changed over time. Note that by interacting Council membership and U.S. alliance with

year fixed effects, we are allowing the influences of each to be fully flexible over time. Thus, our

main interaction effect is only driven by variation in news coverage that systematically varies with

alliance and Council membership that is not captured by this rigorous set of controls. Column (4)

is our baseline specification.

Interpreted within our framework, the positive estimates of the Council main effect in columns

(1)-(2) show that reader demand effects are present in our context. The negative interaction effects

in columns (1)-(4) show that government distortion is also present. To assess the magnitude of

the estimated distortion implied by the coefficients in column (4), we compare the effect of Council

membership for a country that is on the 75th percentile of the distribution of U.S. alliance that

votes with the United States on approximately 10.6% of divided issues on average (e.g., Ecuador,

Egypt) to a country that is on the 25th percentile of the distribution of alliance that votes with

the United States on approximately 4.3% of divided issues on average (e.g., Mali, the Republic of

Congo). This is shown at the bottom of the table. We find that Council membership of the stronger

ally will result in 42% (−6.62 × (0.106 − 0.043) = 0.42) less coverage relative to membership of the

weaker ally.

Another way to assess the magnitude of the estimates is to ask how strong alliance needs to

be for Council membership to reduce news coverage, and how many countries in the sample were

sufficiently allied to experience this reduction. For this back-of-the envelope calculation, we use the

estimates in column (2), which show that the uninteracted coefficient for Council membership is

0.43 and the interaction coefficient is -5.04. This implies that a country that votes with the United

States on 8.5% or more of divided issues will experience a reduction in news coverage when entering

the Council (5.04/0.43 = 0.085), which applies to 39% of the countries in our sample.

24

6.2 Sensitivity

6.2.1 Alternative Measures of News Coverage and Sample Restrictions

In column (5), we examine the number of news articles (without logs) as the dependent variable.

The estimates are similar in sign and statistically significant at the 10% level. The differential effect

on the 75th percentile and 25th percentile allies shown at the bottom of the table imply that

Council membership will result in approximately eight fewer stories for the stronger ally relative to

the weaker one.

In Column (6), we examine a dummy variable that equals one if there is at least one news

article about country i’s human rights abuses in year t (in any newspaper). This reveals whether

the main results are driven by changes in news coverage for countries that are typically not covered

by U.S. newspapers (i.e., the extensive margin), or changes in the number of stories for countries

that already receive some coverage (i.e., the intensive margin). The estimate is similar in sign, but

is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

In column (7), we return to examining the main outcome variable, the log of the number of all

news articles, but restrict the sample to country-year observations that have at least one article.

The estimated interaction effect is nearly identical to our main estimates in magnitude, sign and

precision. In column (8), we restrict the sample to countries that are covered at least once during

the sample period. Again, the estimates are nearly identical to the baseline. The estimates in

columns (5)-(8) show that our estimates are more precisely estimated for countries that typically

receive some news coverage of human rights abuses, which may simply reflect the fact that these

are the countries with governments that commit human rights abuses.

In column (9), we check that our estimates are not solely driven by the countries with the worst

or best human rights practices by dropping the five percent of countries that have the worst practices

and the five percent with the best practices. Specifically, we drop countries with highest or lowest

5% average (over the sample period) PTS scores according to either the U.S. State Department or

Amnesty PTS scores. The estimates in column (9) show that our main results are very robust to

excluding the countries with the best and worst human rights behavior from the sample.

In column (10), we restrict the sample to the years of the Reagan Administration (1980-1988),

from which most of the case evidence we presented earlier are from. As expected, the estimates are

25

very similar to the main results.

In column (11), we restrict our sample to countries that were on the UNSC at least once during

our sample period. The estimates are similar to the baseline, which shows that the baseline estimates

are not driven by countries that were never on the Council.

In column (12), we estimate an alternative specification to examine whether the relationship

between alliance and UNSC membership is monotone across alliance levels. For this exercise, we

divide countries into five equally sized groups according to how closely they are allied to the United

States. We then interact each of the five alliance dummy variables with UNSC membership. Since

we include all five interactions, we exclude the UNSC membership main effect, which is collinear.

We exclude the interactions of UNSC and year fixed effects and U.S. alliance and year fixed effects.

The estimates show that the coefficients are indeed monotonically declining with alliance. The

pattern across coefficients is consistent with our model. The interaction terms for the weakest and

strongest alliance groups are significant at the 1% level.

6.2.2 Timing of the Effect

Interpreting the association between the interaction of UNSC membership and U.S. alliance