Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

1

Department of Rehabilitation Services

Physical Therapy

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

ICD 10 Codes:

F44.4 - Functional neurological symptom disorder with abnormal movement

F44.4 – Functional neurological symptom disorder with speech symptoms

F44.4 – Functional neurological symptom disorder with swallowing symptoms

F44.4 – Functional neurological symptom disorder with weakness or paralysis

F44.5 – Functional neurological symptom disorder with attacks or seizures

F44.6 – Functional neurological symptom disorder with anesthesia or sensory loss

F44.6 – Functional neurological symptom disorder with special sensory symptoms

F44.7 – Functional neurological symptom disorder with mixed symptoms

F44.4 - Conversion disorder with motor symptom or deficit

Case Type / Diagnosis:

Overview of Functional Neurological Disorder:

Functional Neurologic Disorder (FND), also known as Functional Movement Disorder, is an

acquired neurologic dysfunction that accounts for over 16% of patients referred to neurology

clinics.

1

It is characterized by abnormal motor behaviors that are inconsistent with an organic

etiology.

2

While other terminology has been used to denote this diagnosis (e.g., conversion

disorder or psychogenic disorder); such nomenclature implies only a psychological cause. As a

result, the most accurate and current terminology is to describe the condition as one that is

functional.

3-4

This disorder sits at the intersection of neurology and psychiatry and is not yet well

understood on a pathophysiological level. Patients typically present with a sudden onset of

symptoms that may include limb weakness, limb paralysis, gait disorder, tremor, myoclonus,

dystonia, or sensory or visual disturbance. FND can be triggered by a physically traumatic or

psychological event, but does not always manifest this way. Symptoms of FND differ from those

of progressively degenerative movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s Disease, in that they

oftentimes come on rapidly and intensely with periods of spontaneous remissions.

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

2

Etiology:

The etiology of FND is not known. In the past, FND had been described as a physical

manifestation of psychological distress. Now, many cognitive and neurobiological models are

being considered as a cause of FND. Some researchers have proposed that FND is caused by a

combination of increased emotional arousal in the amygdala at symptom onset and a “previously

mapped conversion motor representation,” possibly as a result of a prior physical or

psychological precipitating event.

5-6

They suggest that the “previously mapped conversion motor

representation” is triggered and cannot be inhibited due to abnormal functional connectivity

between the limbic structures and the supplementary motor area and higher activity in the right

amygdala, left anterior insula and bilateral posterior cingulate.

5

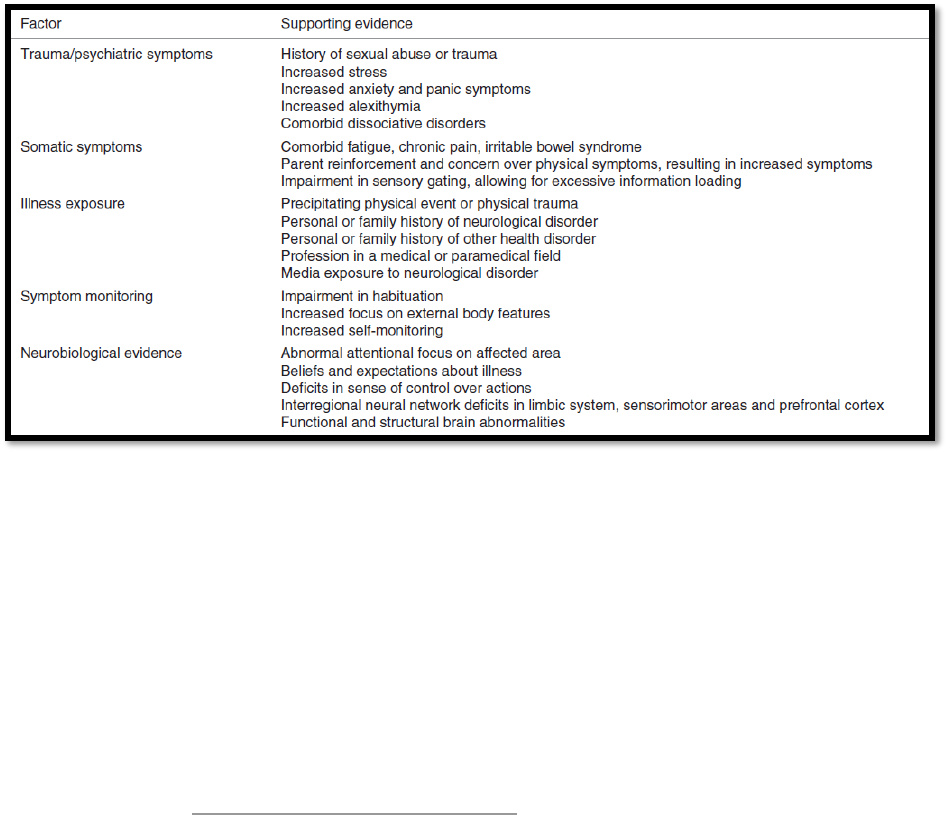

Research has shown that there

are a vast array of vulnerabilities that may predispose an individual to FND. Table 1 from

Fobian & Lindsey, 2019 details some possible factors that may make a person more susceptible

to FND. Individuals may present with one or any combination of these characteristics.

5

Table 1: Overview of FND Predisposing Factors

Prevalence:

FND has an incidence of 4 to 12 per 100,000 population per year in the United States. In a study

including outpatients of neurology clinics, 5.4% of patients had a primary diagnosis of FND,

while 30% had symptoms described as only somewhat or not at all explained by other organic

disease. Overall prevalence of FND is higher in women; women make up 60-75% of the FND

patient population.

7

Symptoms:

Symptoms of FND vary widely. Patients may present with limb weakness/paralysis, gait

disorder, dystonia, tremor, functional tremor, myoclonus, sensory or visual disturbances, in

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

3

addition to several other potential symptoms. Typically, these symptoms disappear with

distraction and increase with attention. In addition, Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures (PNES) is

another FND presentation. Patients presenting with this condition experience seizures without

any accompanied Electromyographic (EMG) activity or Electroencephalographic (EEG) changes

shown to indicate epileptic activity. If possible, video EEG tests are indicated for patients with

PNES. Capturing a seizure-like episode on video EEG that is not associated with epileptiform

activity is currently the gold standard for this diagnosis.

7

However, this may not be accessible to

every patient. Another symptom of FND can also be Persistent Postural Perceptual Dizziness or

PPPD, which is perceived unsteadiness, and/or dizziness without vertigo.

Diagnosis:

In the past, FND was typically diagnosed by identifying a precipitating trauma or stressor in

combination with inorganic movement pattern. Today, positive signs are the key indicator of a

phenotype-based diagnosis.

7, 8

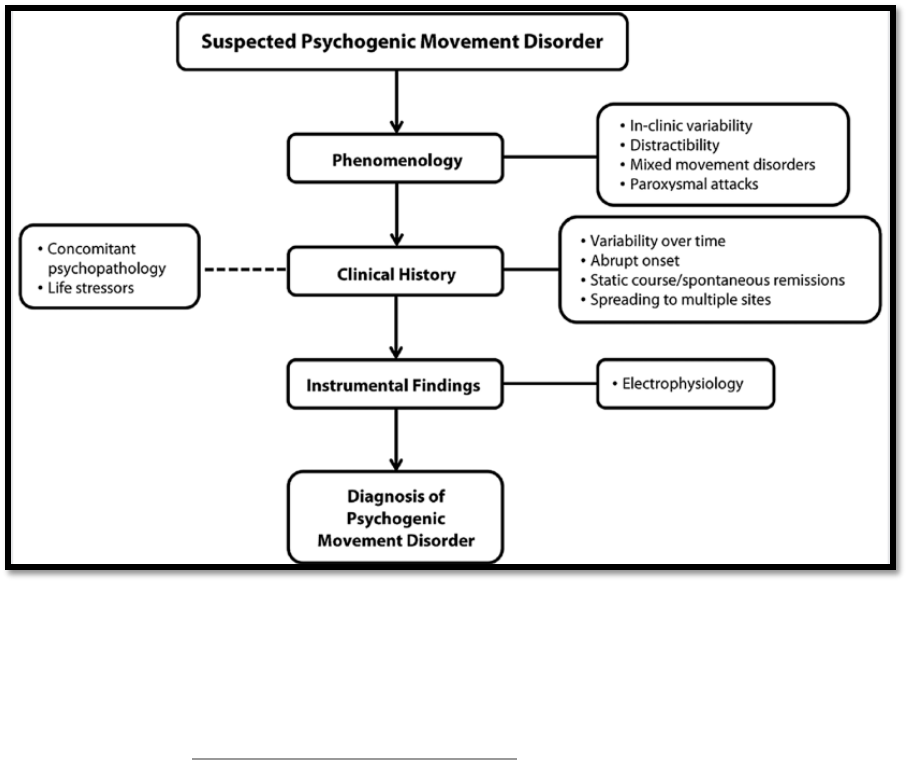

Figure 1 from Morgante, Edwards & Espay, 2013 includes a

potential algorithm for diagnosing movement disorders, while Box 1 from Espay et al, 2018

shows common positive symptoms associated with a diagnosis of FND.

7, 9

Figure 1: Proposed algorithm when diagnosing FND. Diagnosing FND is a multistep process

that should integrate observed phenomenological features, the patient’s clinical history, and any

instrumental findings. In addition, any relevant history pertaining to the patient’s

psychopathology should be carefully reviewed either with the patient or in their chart (dotted

line).

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

4

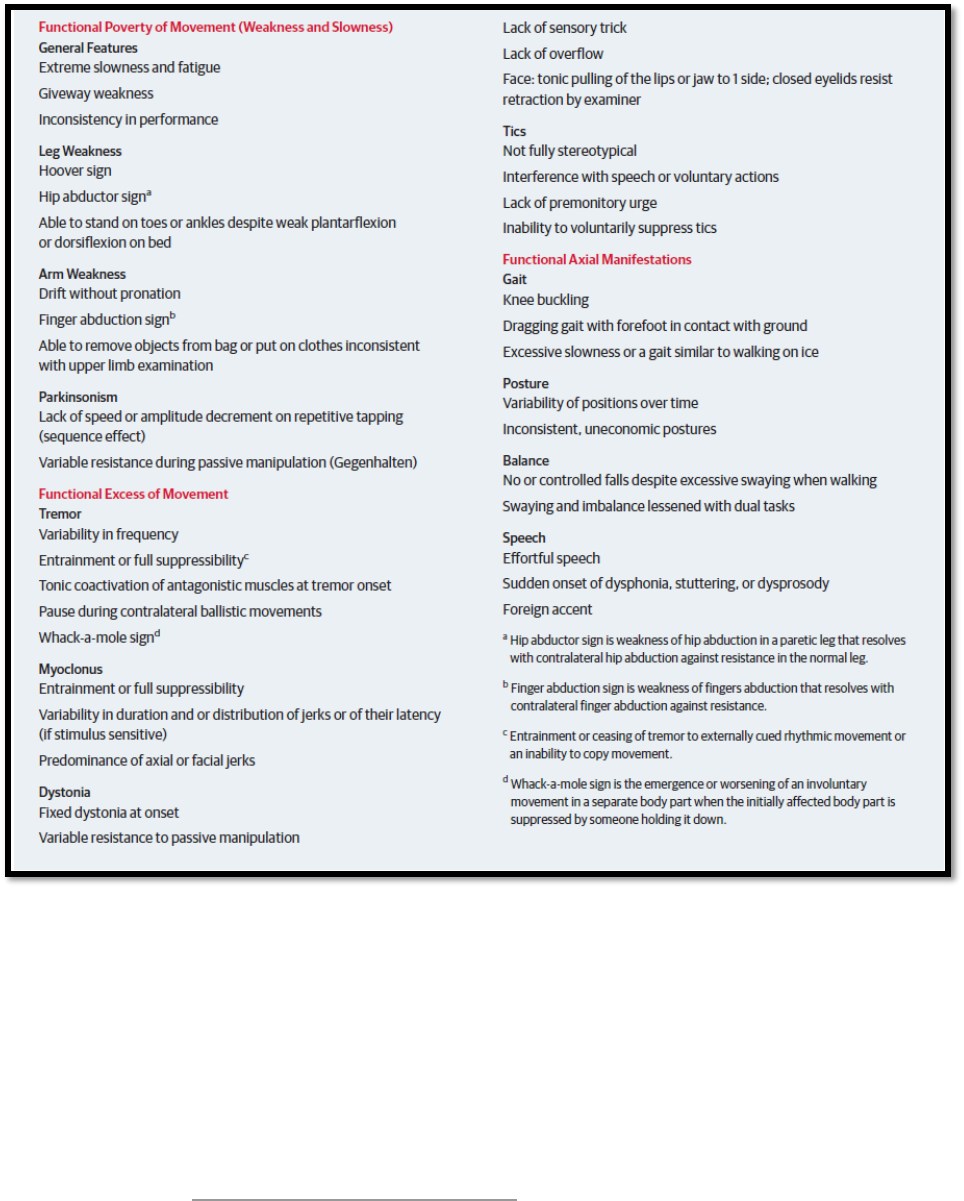

Box 1: Common Clinical Features of Functional Movement Disorders

Prognosis:

The consensus for treatment of FND includes a comprehensive care approach. Physical therapy

(PT) is an important and beneficial part of the recovery process. The overall prognosis for FND

depends on the level of impairment, time of diagnosis and length of symptom duration. The

longer a person goes without an official FND diagnosis, typically the worse the prognosis.

Taking unnecessary medications can also negatively affect prognosis.

5, 10

Furthermore, people

who have decreased levels of health literacy have a poorer prognosis. Typically, people with

FND can experience relapses; physical therapy can help to provide patients with strategies to

manage and deal with these relapses.

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

5

Indications for Treatment:

Patients with a diagnosis of FND may or may not be referred to physical therapy initially.

Patients with FND are appropriate for physical therapy when there is a motor component to their

disorder or they are experiencing PPPD. In addition, patients are more likely to benefit from

physical therapy if they have a good understanding of their FND diagnosis and are motivated to

improve. Improved buy-in to physical therapy has also been linked to better outcomes.

11

Contraindications / Precautions for Treatment:

While working with patients with FND, physical therapists must always be aware of general

contraindications for exercise such as abnormal heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation

levels, etc. While not a specific contraindication or precaution, it is recommended that patients

receive a diagnosis of FND from a neurologist prior to beginning a course of physical therapy for

optimal results.

11

If the patient has not been diagnosed with FND and the treating physical

therapist suspects that a patient’s impairments are due to FND, the patient should be referred to a

neurologist familiar with functional disorders for further examination.

Other precautions include if a patient does not agree with the FND diagnosis, if they are focused

more on other elements of their disability, such as an upcoming litigation or disability

paperwork, that they are unable to fully participate in therapy, or if a patient is not buying into

physical therapy.

4, 11, 12

While suspected malingering would certainly be an additional precaution

for treatment,

malingering has been shown to be very rare in the FND population.

6, 13, 14, 15

Medical History/History of Present Illness:

It is essential to first review the patient’s medical record, medical history and any medical

questionnaires as reported on paper or in Epic. Review any recent medical imaging, tests, or

operative notes. In addition, the following information should be gathered while compiling the

patient’s history that specifically pertains to FND:

• Initial onset and initial symptoms

• Current symptoms

o Can include limb weakness/paralysis, gait disorder, dystonia, tremor, myoclonus,

sensory disturbances, visual disturbances

• Frequency and day-to-day variance of symptoms

• If there is a pattern to symptoms, i.e. right sided vs. left sided, triggered with certain

motion or action

• History of concussion or TBI

• Precipitating emotional event or stressor

• Recent illness, surgery, or hospitalization

• Level of function prior to FND symptoms/diagnosis

• What led the patient to physical therapy

• Discuss if patient has received any formal diagnosis and, if so, how it was explained to

them

• If the patient has been formally given a diagnosis of FND, ascertain what is their

understanding, expectations, and understanding of the diagnosis. Julie Maggio, PT at

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

6

Massachusetts General Hospital created the following set of questions to be asked to

patients being evaluated with FND. Their responses can inform clinical impressions as

well as guide patient education during treatment sessions.

o Patient’s Understanding of Diagnosis

▪ How well do you think you understand this diagnosis, rate 0 to 10? (0, not

at all to 10, full understanding)

o Patient’s Acceptance of Diagnosis

▪ Which statement most accurately represents your current acceptance of

this diagnosis?

▪ I do not think the diagnosis of a FND is correct. I think there is

something else wrong with me.

▪ I am willing to think about FND as a diagnosis for my problems

but am still not sure it is correct.

▪ I think the diagnosis of FND is the correct diagnosis.

o Patient Expectations

▪ To what extent do you expect to recover from this diagnosis, 0 to 10? (0,

not at all to 10, full recovery)

Social History and Prior vs Current Level of Function:

• Home environment/setup

• Assistive devices or other equipment

• Family and social support systems

• Occupation

• Family role

• Community role

• Current and previous exercise routine and leisure activities

• Sleep regiment

Medications:

FND has not been shown to be effectively managed through medication.

6, 10

However, patients

may be taking other medications for different diagnoses. With these medications, it is important

to note:

• Name, dose, time taken

• Any possible side effects that may interfere with physical therapy

Examination:

Functional Mobility Assessment:

If possible, try to assess patient’s gait and movement patterns informally (while they are in the

waiting room, walking back to exam room, leaving evaluation) as well as formally in your

examination. Be sure to document thoroughly and specifically on patient’s functional movement

impairment/presentation. In addition, if diverted attention strategies are implemented as part of

the evaluation, document the change in performance with quantitative and qualitative

descriptors.

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

7

• Gait: assess both with and, if able to do safely, without patient’s assistive device

• Stair Navigation: if stairs are part of the patient’s normal routine, assess stair navigation

by recreating a similar setup to the patient’s home environment. Stair navigation can be

an important assessment tool, as the automatic, repetitive motion of stairs may cause

symptoms to decrease.

11

• Transfers: assess both with and, if able to do safely, without patient’s assistive device

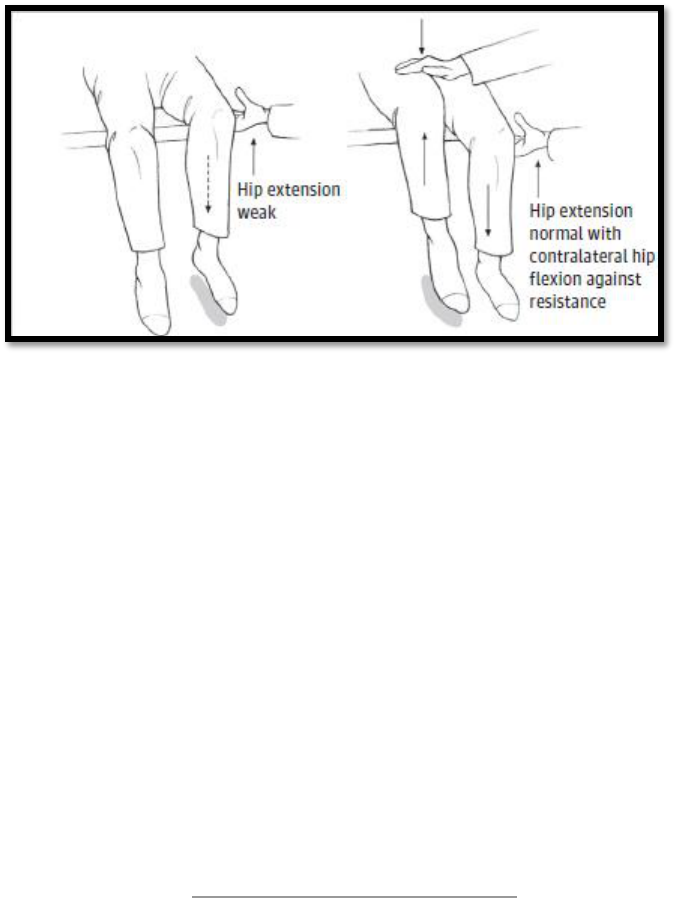

Hoover’s Test: to assess functional leg weakness; the patient may have difficulty pushing their

affected leg down (hip extension), but when they are asked to lift up their unaffected leg,

strength in the affected leg returns to normal. Figure 2 from Espey et al 2018 demonstrates a

positive Hoover sign when tested in the sitting position.

7

Figure 2: Hoover sign testing for functional leg weakness

Tremor entrainment test: to assess for functional tremor; this is when the shaking of a limb

becomes momentarily better either when the person concentrates on mirroring a movement made

by the examiner in either the affected limb or in another body part, or when they are asked to

copy a rhythmical movement with their unaffected limb. The clinician can then assess if the

tremor in the affected hand either ‘entrains’ to the rhythm of the unaffected hand, stops

completely or the patient is unable to copy the simple rhythmical movement.

Pain: record location and descriptors (shooting, throbbing, sharp, dull, ache, etc.) of pain, and

pain score on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS); patients with FND may or may not have pain.

Palpation: If patient has pain, palpate painful areas to assess for any tenderness or tissue

sensitivity.

ROM: If range deficits exist, measure and document appropriately. Compare to opposite

side/limb.

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

8

Strength: A general Manual Muscle Test (MMT) screen should be completed of both upper and

lower extremities to note any inconsistencies. Test specific muscles of both left and right limbs

with the functional abnormality. Note any inconsistences between patient performance on MMT

and functional activities. These and other inconsistencies in physical presentation can be used to

help explain to the patient that their nerves/muscle are working and intact; they just do not

currently have full control over them.

Sensation/Proprioception: Changes in sensation are possible with FND. This can include loss

of sensation, abnormal sensation or pain. Of note, sensory changes are often “splitting of

midline” that affect half of the patient’s face, trunk, or limbs. If patient presents with sensation

abnormalities, assess light touch, and vibration sense. Patients with FND may also present with

proprioception impairments. This can be tested by having the patient close their eyes while the

PT positions a joint (big toe, ankle, knee, forearm, etc.) in space. A patient with intact

proprioception will be able to correctly identify what position the joint is in (i.e. bent vs.

straight).

Coordination: Patients with FND may present with coordination impairments. If indicated, a

full coordination exam should include assessment of rapid alternating movements, finger to nose

accuracy, finger to target accuracy, and postural stability.

Vestibular/Oculomotor Screen: Patients with FND may have oculomotor or vestibular

dysfunction. An oculomotor exam may be indicated and would include an assessment of:

extraocular motion (EOM), smooth pursuit, saccades, and for the presence of spontaneous and

gaze evoked nystagmus with and without fixation. Other tests may include Vestibulo-ocular

Reflex (VOR) testing via the Head Impulse/Thrust Test and cancellation of the VOR (VORc).

Other vestibular tests may also be appropriate pending patient’s presentation and symptom

complaints. Please refer to the Peripheral Vestibular Hypofunction Standard of Care for further

details on vestibular and oculomotor tests and measures.

Functional Outcomes: While there are no set outcome measures established in the literature to

track progress for patients with FND, instruments that assess patient level of function (or

perceived disability), their quality of life, their objective motor performance, and their overall

function are commonly implemented. Moreover, using several outcome measures may be

beneficial to more fully encompass the patient’s impairments and the effect on his/her life.

Given the variety of presentations seen with patients with FND, the specific outcome measures

used will likely vary on an individual level. Examples of suggested outcome measures include:

Short Form Health Survey - 36 (assesses patient quality of life, with both a physical and mental

health component), PHQ - 15 (assesses severity of symptoms), 10 Meter Walk Test, Timed Up

and Go, Five Times Sit to Stand, and the 2 Minute Walk Test.

16-17

Differential Diagnosis:

Although physical therapists do not formally diagnose patients with

FND, they may be the first clinicians to recognize signs and symptoms in a patient. When that is

the case, the patient should be referred to a neurologist who treats patients with FND for a full

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

9

workup. While this list is not exclusive, these are conditions that may present similarly to FND

obtained from Stone et al 2013.

18

• Higher cortical gait disturbance

• Acute parietal stroke/pathology

• Stiff person syndrome

• Tics/Tourette’s

• Contractures in fixed dystonia

• Myasthenia

• Paroxysmal dyskinesia

• Parkinson’s Disease

• Multiple Sclerosis

Assessment:

Problem List:

• Impaired strength/motor control

• Impaired balance/postural control

• Impaired ROM

• Impaired sensation

• Impaired gait

• Impaired functional mobility

• Impaired aerobic capacity/endurance

• Pain

• Oculomotor impairments

• Dizziness

Goals:

Create goals that are attainable and incorporate the patient’s own goals. Goals should be

measurable and within a specified time period. The time frame may vary depending on the

patient’s functional status, psychosocial factors, and extent of condition. Goals can include:

• Optimizing and normalizing gait

• Maximizing independence during functional mobility

• Focusing on specific impairments i.e. improving ROM, muscle performance, strength,

coordination or endurance, etc.

• Creating a home exercise program that is attainable and feasible for the patient to perform

on a regular, consistent basis

• Educating the patient on the diagnosis of FND and symptom management strategies to

facilitate normalization of movement

Treatment Planning / Interventions:

Patient education:

There has been much debate with regards to treatment of FND, given the variety of

presentations. In all cases, however, the most crucial underpinning of FND treatment across

disciplines is assessing the patient’s understanding of the diagnosis, acceptance of the diagnosis,

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

10

goals, and expectations for recovery.

4

While other health care providers may have already

discussed the FND diagnosis with the patient, it is crucial to assess and optimize their health

literacy on the subject by clarifying any terminology and the pathophysiology of the diagnosis.

Namely, it is important to stress that, while the patient’s nervous system is not currently

functioning correctly, there is no structural defect or lesion.

4, 11

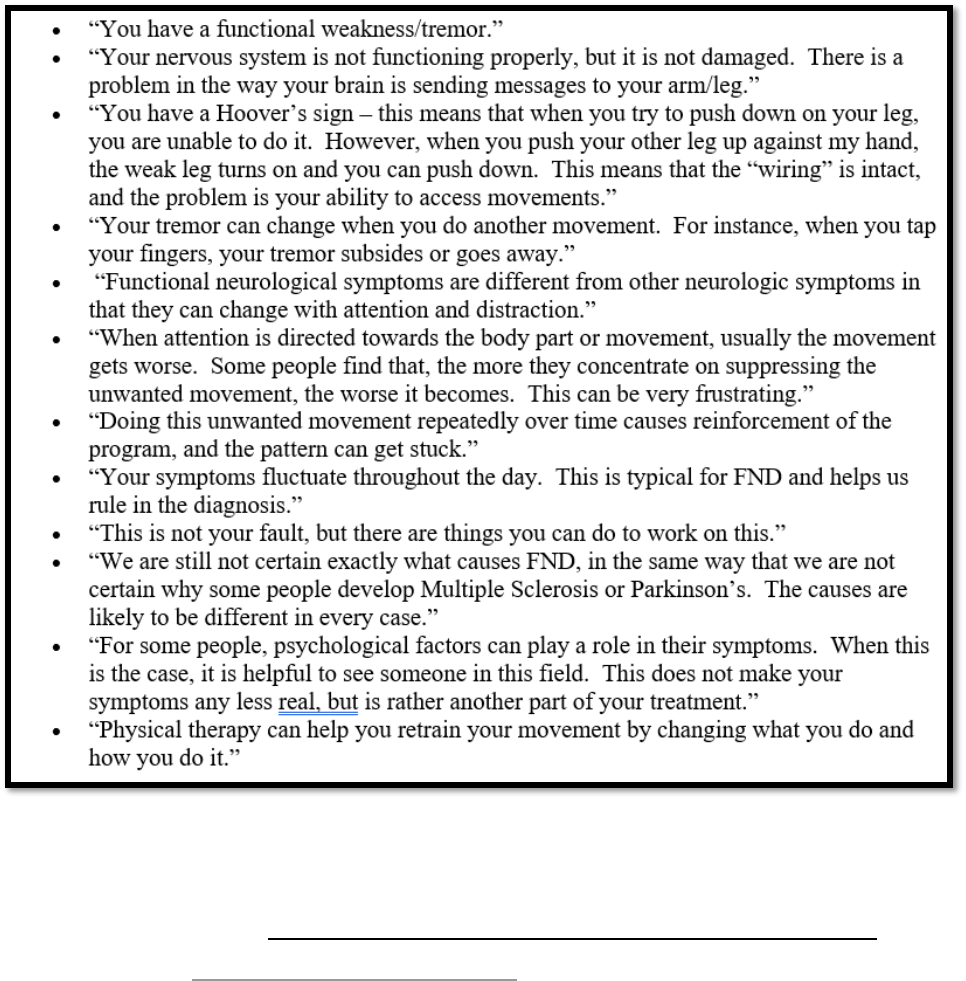

Table 2 provides examples

compiled from Nielsen et al 2014, Nielsen 2016, Maggio & Parlman 2019 on patient-appropriate

language when explaining their diagnosis.

4, 11, 17

Table 2: Patient-Friendly Examples when Explaining FND and the Role of Physical Therapy

Use written resources to solidify topics discussed with the patient and to allow them to

further explore their diagnosis independently. This will help them to further their own

understanding of their condition. For example, neurosymptoms.org, www.fndhope.org,

www.fndaction.org.uk, and Overcoming Functional Neurological Symptoms: A Five Areas

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

11

Approach

19

are useful tools health care professionals can utilize to facilitate patient education

and that patients should be encouraged to utilize independently.

In addition, it is crucial to reinforce a patient’s normal results seen on exam as well as

reiterate that there is no structural or anatomical lesion. One common tool utilized in FND

literature is to describe the disorder as a “software problem” of the nervous system, as opposed

to damage to the “hardware”.

3, 4, 11

Furthermore, explaining to the patient how a variety of factors

that can trigger FND and the importance of working with multiple health care providers across

disciplines to address their symptoms will help promote the importance of interdisciplinary care

and collaboration.

Finally, it is essential to frame this discussion with the explicit understanding that their

diagnosis and presenting symptoms are both common and real. It is important to encourage them

that physical therapy has been effective for other patients with FND in re-training the nervous

system to help gain back control of their movement patterns. FND should never be described as

a diagnosis of exclusion, but rather one that is comprised of specific clinical features, such as a

positive Hoover’s sign or tremor entrainment.

3, 6

Moreover, using language such as “functional”

over vocabulary such as “conversion”, “somatization” and “psychogenic” can help to reframe

this condition from psychological towards one in which biopsychosocial factors have manifested

into physical symptoms.

4, 20

Clinicians should emphasize that, while these symptoms are

“learned movement patterns,” and thus amenable to treatment, they are also outside of the

patient’s control.

4

For example, patients can be shown their Hoover’s sign or tremor entrainment

to illustrate the potential of reversing their presented symptoms or impairments.

21

By framing

FND as a miscommunication between the brain and the body that manifests in tangible

symptoms that have the potential of reversibility, clinicians can both acknowledge the validity

and existence of these symptoms, while also instilling patient confidence in the role of

rehabilitation.

Interventions most commonly used:

Given the vast variety of clinical presentations as well as the various settings where a patient can

be treated and their frequency and duration guidelines, specific interventions will vary widely.

However, below are several treatment strategies compiled from various literature on how to

guide treatment sessions:

• Limit “hands on” treatment – although the majority of these patients seem to present as

fall risks, it is essential to foster patient independence and increased confidence in their

ability to perform certain activities. For example, when a patient is performing a transfer,

avoid manually assisting them as much as possible or donning a gait belt, as the patient

will likely anticipate that they will be unable to perform this activity and promote

avoidance patterns.

4, 11, 17

Instead, encourage them to try on their own initially and that

you have confidence that they can be successful.

o Of note, the risk of falls in the FND population is somewhat controversial. It is a

common perception that, despite presented weaknesses, tremors, or gait

abnormalities, patients with FND typically will not suffer falls.

4, 11

Instead, it is

thought to be more likely that these patients will either maintain their balance or

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

12

demonstrate a controlled descent pattern. With patients for whom it has been

determined to be safe, it is advised to encourage patient independence and limit

unnecessary assistance or restrictions. However, studies have reported that

injuries can occur because of falls in this population,

22

and thus clinicians should

closely examine a patient’s balance during the initial examination and, more

importantly, in response to tasks or exercises prescribed to a patient during

treatment sessions. Based on their response, interventions can then be optimally

tailored to best challenge the patient while also ensuring their safety.

• Facilitate patient control over movement patterns – the literature has shown that

patients tend to overestimate the presence of a functional tremor, when compared to

objective measurements chronicling their symptoms.

11

Instead, functional tremors are

rarely continuous and typically will greatly lessen or cease completely when the patient

stops attending to it. As a result, patient movement patterns should be observed in the

context of other environments and activities (i.e. in the waiting room, throughout their

exam, while conversing, when performing a certain cognitive or motor task, such as when

answering a questionnaire or throwing a ball, etc.) and making note of how their

movement patterns change. Explaining and demonstrating to the patient how their

movement can normalize or minimize can aid in guiding treatments to best address their

symptoms. Videotaping patients can also help reinforce these patterns with tangible

evidence.

4

When treating patients who present with unwanted movement patterns or

tremors, a key approach is to encourage voluntary control of the involuntary pattern. For

example, instructing a patient to actively mimic their tremor and progress towards

decreasing the frequency as well as consciously eliminating and ceasing the tremor for a

period of time.

17

In addition, incorporating visual feedback (such as performing an

exercise in front of a mirror) can instill a sense of control in the patient.

2, 4, 11

• Addressing maladaptive movement patterns – physical therapists can distinguish and

work to change any maladaptive behavior patterns that exacerbate patient symptoms. For

example, patients may present with certain avoidance patterns or with “all or nothing”

behaviors that reinforce unwanted symptoms.

11, 23

Through an ongoing discussion with

patients and their family, clinicians can create activity modification strategies to instill

patient independence while also avoiding any stressors that may exacerbate symptoms.

Utilizing concepts such as the “mind body overload” can engage the patient in possible

psychological/behavior components to their diagnosis that affect their motor symptoms

and encourage the patient to find time to prioritize themselves and their own well-being.

24

• Redirect attention – exploring different variables that trigger or control movement

strategies can be a helpful tool. For example, some patients find that an added cognitive

task can help to minimize or eliminate their symptoms, such as having a conversation,

counting, reading a book, writing, or listening to music. In addition, diverting attention

from abnormal movements through activities performed simultaneously with uninvolved

limbs can be helpful. Examples include tapping the uninvolved lower extremity or

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

13

clapping hands together while walking, snapping fingers, twirling a stone, or moving

keys in their pocket.

• Sequential learning – one common approach towards retraining movements is to return

to the basic components of a movement task that a patient can perform without any

symptoms and then slowly progress to reshaping normal patterns.

2, 11, 25

One example of

this is to begin to address a functional gait disorder by initially focusing on gentle weight

shifting, which can then be progressed towards unweighting each foot, and then slowly

incorporate advancing each limb in a smooth and reciprocal manner.

4

This approach

enables the therapist to help retrain a patient’s movement without utilizing any unwanted

maladaptive movement patterns. As the patient is mastering the task, clinicians should

utilize motor learning principles such as repetition, appropriate feedback that encourages

learning, and gradually increasing the difficulty of the task by altering the environment

(open vs closed), speed, and cognitive demands.

4, 26

• Gradually eliminating external support – it has been shown that muscle weakness is

rarely a problem with FND, but rather the patient presents with deficits in movement

control.

4

Moreover, utilizing a walking aid may trigger overdependence and could

possibly result in secondary impairments such as deconditioning.

4

Physical therapists

should instead encourage lower limb weight bearing to promote automatic activation of

proximal musculature and facilitate patient independence. If the patient does require

additional support for safety, utilizing a counter top can allow the therapist to gradually

reduce the amount of external support (progressing from bilateral hand support to one

finger support) as the patient performance improves. In addition, by preventing the

patient from putting excessive weight through a device and instead demonstrating to them

that they can successfully stand with just finger-tip support, the patient will build

confidence in their capabilities.

• Encouraging self-management – as with any pathology addressed in the physical

therapy setting, patient self-management of symptoms is essential towards instilling

patient confidence and facilitating successful outcomes. Utilizing the workbook

Overcoming Functional Neurological Symptoms: A Five Areas Approach or encouraging

the patient to write in a journal can facilitate improved patient mindfulness and self-

awareness of their condition.

19

Contents can include (but are not limited to): patient

reflections on their diagnosis, maladaptive patterns and any aggravating factors to their

symptoms, useful strategies employed during treatment sessions that can alleviate or

manage their symptoms, prescribed exercises (and participation rates), and their goals

(and the progress they have made towards these goals).

4,

27

In addition to specific interventions to address the patient’s presenting impairments, as

many patients also present with a level of deconditioning due to decreased activity participation,

non-specific graded exercise can address reduced exercise tolerance.

4, 11, 28

Moreover, graded

exercise has been associated with improved outcomes in patients who present with chronic pain,

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

14

which is a common symptom in many patients who present with FND.

29

Clinicians should tailor

intensity of exercises based on the patient’s response in order to appropriately challenge the

patient without exacerbating their symptoms. Table 3 lists interventions cited in different

literature on specific treatment ideas when patients present with specific impairments.

4, 11

Table 3: Intervention Techniques Targeting Specific Symptoms of FND

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

15

Frequency & Duration:

While studies have varied in terms of frequency and duration recommendations, generally it is

appropriate to see patients 1-2 times per week for a duration of 12-16 weeks.

11

However, if

patients live far from the clinic, the frequency can be altered to fit their specific needs. Generally,

it is beneficial to see these patients for a full hour due to the complexity of their presentation. As

the patient progresses, their frequency and duration can be modified to best suit their specific

needs.

Patient/Family Education:

As previously discussed, patient education is vital when treating FND. In addition, their friends’

and family’s knowledge and buy-in of the diagnosis can greatly affect the patient’s prognosis and

the benefit of therapy on their symptoms. In addition, clinicians should share key treatment

principles and successful strategies employed in the clinic as well as the importance of reducing

reinforcement of atypical movement patterns to encourage patient independence as much as

possible.

11

Oftentimes, caregivers will assist the patient at a greater level than needed to avoid

perceived risks or harm to the patient. However, this may decrease a patient’s level of confidence

as well as potentially affect the patient-caregiver relationship due to increased strain or caregiver

burnout. While family support is essential and should always be encouraged, it is important for

the patient and family members to understand that the patient needs to practice difficult and

challenging tasks in order to improve. Ideally, this will ultimately lead towards increased patient

independence and facilitate positive and healthy relationships between the patient and family.

30

Interdisciplinary Collaboration/Care:

• Neurologists - As mentioned above, patients who first receive a clear diagnosis of FND

by a physician prior to starting physical therapy are more likely to achieve optimal patient

outcomes. Most often, this physician is a neurologist who has conducted a thorough

neurological exam and relayed clinical findings that rule in the diagnosis to the patient.

Physical therapists should communicate closely with the patient’s neurologist to assess

and share the patient’s understanding and confidence in this diagnosis. Without a

confirmed diagnosis from a neurologist and acceptance from the patient, it is very

unlikely that a patient will make effective progress with physical therapy.

31

• Occupational Therapists (OT) – While there is limited published literature on evidence-

based assessment and treatment guidelines, it has been repeatedly indicated that

occupational therapy is an integral member of the health care team when it comes to

effectively treating patients who present with FND.

2, 6, 7, 13, 23, 30, 32, 43

Occupational

therapists address the physical and psychological barriers inhibiting success in daily

activities through engagement in functional activities.

30

More specifically, occupational

therapists are trained in mental health training and facilitating patient participation in

functional activities, which can aide in symptom management, coping strategies, and

changing behavior patterns to improve function.

32

In addition, patients with FND often endorse sensory modulation dysfunction.

The Sensory Integration Theory was developed by Jean Ayers in the 1970s and is defined

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

16

as an individual’s ability to process sensory information both within himself or herself as

well as in the external environment to adapt and interact effectively in their daily life.

33

Individuals require intact sensory modulation to respond to sensory stimuli with an

appropriate behavioral response. Impaired sensory modulation can occur when sensory

stimuli do not invoke a specific graded behavioral response, leading to an array of

maladaptive emotional responses, poor learning, and decreased cognitive performance.

For example, many individuals with FND will complain of hypersensitivity to sounds,

moving targets, and crowded environments, and have limited coping strategies to combat

their sensitivity.

32

Sensory-based interventions can thus aid in improving sensory

processing, body awareness, and emotional regulation, as well as promoting normal

movement patterns.

30

Moreover, occupational therapists can work with patients to

implement specific interventions that can successfully modulate sensory information

during daily activities as well as incorporate sensory tools and strategies that a patient can

use when they are symptomatic or are experiencing early warning symptoms of a

psychogenic nonepileptic seizure. These tools and strategies can lead to improved

participation in daily activities and responsibilities and help facilitate patient control over

their symptoms.

• Speech-Language Pathologists (SLP) – Functional Speech Disorder (FSD) is reportedly

seen in up to 50% of patients diagnosed with FND.

34, 35

While clinical features can range

widely, patients with FSD may present with disfluency, stuttering, foreign accent

syndrome, childlike speech, and inconsistent hypernasality, all in the absence of any

anatomical lesion or aphasia.

35, 36

In addition, patients diagnosed with FND may present

with swallowing, language, and cognitive disorders, which also fall under the scope of

SLP practice. Speech-Language Pathologists can work with patients to increase their self-

awareness of their speech impairments, modify their speech output, and support

carryover across various communication settings.

• Psychiatrists/Psychologists – When patients present with psychogenic nonepileptic

seizures (PNES), it is essential that a trained neuropsychiatrist work with them to address

patient control over their seizures. As mentioned above, patients with FND are generally

more likely to have a psychiatric comorbidity when compared to the general population

and may also benefit from specialized psychiatric treatment.

37, 38

Different approaches to

treating patients with PNES have been used with good results, including Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy (CBT), CBT-based self-guided help via workbooks, psychodynamic

therapy, hypnosis, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMRD).

39

In a

recent RCT of 66 patients with dissociative seizures, it was shown that CBT plus

standard medical care (SMC) was superior to SMC alone.

40

Specific intervention

approaches mentioned in the study include intervening when patients began to exhibit

warning signs indicative of a future seizure, reducing certain avoidance patterns, and

helping address maladaptive thoughts and behavior patterns related to patient’s self-

esteem, well-being, and ability to control their seizures. Of note, anti-epileptic drugs are

not typically given to treat PNES, and some studies have instead observed a harmful

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

17

effect when prescribing patients with medication.

10, 39

In general, medications have a

limited role for FND and their associated symptoms. The one caveat is that patients with

some psychiatric disorders may benefit from medications to best manage those

conditions.

41

• Social Work (LSW) – Many of these patients present with complex biopsychosocial

factors intertwined with their FND diagnosis. A social worker can work closely with the

patient to provide counseling and ensure that they feel adequately supported. In addition,

they can work closely with the patient and their family to ensure that needs are accounted

for and to help the family obtain appropriate resources to optimize the patient’s treatment

and recovery. LSW can also be trained to perform CBT when patients present with

PNES.

Re-evaluation:

A re-evaluation in the form of a progress note is required every 30 days by insurance. If patient

has a change in status, a re-evaluation may be appropriate prior to 30 days. Examples of a change

in status include:

• Patient has a fall which results in injury

• Patient has a significant change in functional level or symptoms

• Goals set by PT at initial evaluation are met prior to 30 days

Discharge Planning:

Commonly expected outcomes at discharge:

It can be very difficult to predict patient response to therapy and the level of function that

they are expected to reach. As a result, this can make the discharge process difficult at times. It is

essential to recognize that, while therapy has been shown to have a proven beneficial role in the

rehabilitation of many patients with FND, these individuals can be a very challenging population

to treat due to the constellation of presenting symptoms, the complex biopsychosocial interplay

within the patient, and the dynamics of their support systems. Failure to progress can be due to a

number of reasons.

Some factors contributing to lack of progress include decreased

acknowledgement/acceptance of the diagnosis as well as decreased buy-in from the patient,

chronicity of symptoms, lack of communication between specialists, decreased patient

participation in their home exercise program/treatment strategies outside of the clinic, and level

of social support.

12, 17, 42

While the patient may not fully return to their previous level of function

at time of discharge, the goal of physical therapy is to improve the patient’s self-management of

symptoms and provide them with a set of strategies on how to promote normal movement

patterns and optimize their ability to participate in activities at home, work, and in their

community. It is also important to note that, if a patient is discharged due to lack of progress,

they could still benefit from physical therapy in the future should some of the above variables

change, such as greater acceptance of their diagnosis and buy-in of the role of physical therapy.

12

As a result, discharge planning should begin at treatment onset to establish expectations

and minimize confusion or frustration between the therapist and the patient. Studies have

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

18

endorsed creating “treatment contracts” on patient attendance and participation as well as inform

the patient on anticipated frequency and duration of physical therapy care.

2, 4, 22

Transfer of Care:

While the intended audience for this standard of care is physical therapists in the

outpatient setting, the underlying themes regarding FND examination and treatment can be

applied across the spectrum of health care settings. Each setting offers unique pros and cons

when treating patients with FND, with regards to frequency and duration of care and available

resources.

43-45

When a patient is transitioning to a different health care setting, health care providers

should communicate closely to facilitate a seamless transition. Documentation should be

thorough when detailing the patient’s history and their clinical examination, imaging, and other

workups. In addition, providers should include information on patient education regarding their

diagnosis and the patient response and buy-in. Finally, documentation should include a summary

of their plan of care, useful resources incorporated, patient responses to different intervention

approaches, health care professions involved in a patient's care team, as well as other health care

professions that a patient may benefit from seeing to allow the next clinician to most effectively

create a treatment plan to maximize their quality of care.

If the patient is going out of network in which documentation may not be relayed

electronically, providing written documents of these different elements to the patient can help to

ensure that future clinicians are fully informed.

Patient’s Discharge Instructions:

As mentioned above, while the patient may not fully return to their premorbid level of function,

the goal should be for patients to have created a “toolbox” of strategies on how to avoid

maladaptive patterns and promote normal movement. As the patient nears discharge, they should

be transitioned into the self-management phase of their treatment, which can be facilitated by

decreasing the frequency of their visits.

11

At the time of discharge, provide patients with a list of

written strategies and exercises to help facilitate independent management. This information

should also be incorporated into the patient’s medical record for other health professionals to

access to illustrate the patient’s progress made in physical therapy and their status at discharge.

As setbacks or relapses can be common with FND, patients should be advised on the importance

of frequent participation in their exercise program and how they can best utilize their exercise

toolbox when they are experiencing a symptom exacerbation.

Authors: Lauren Carter, PT Reviewed by: Kristina Dunlea, PT

Kirby Smith, PT Julie Maggio, PT

Ginger Polich, MD

Kathleen Taglieri-Noble, PT

Rachel Wilson, PT

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

19

REFERENCES:

1. Edwards M., Bhatia K. Functional (psychogenic) movement disorders: merging mind and

brain. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:250-260.

2. Czarnecki K., Thompson J., Seime R., et al. Functional movement disorders: successful

treatment with a physical therapy rehabilitation protocol. Parkinsonism and Related

Disorders. 2012;18:247-251.

3. Stone, J, Carson A, Hallett M. Explanation as treatment for functional neurologic

disorders. In: Stone J, Carson A, Hallett M. Handbook of Clinical Neurology , vol. 129

(3

rd

series) Functional Neurologic Disorders. Boston, MA: Elsevier; 2016: 543-553.

4. Nielsen G. Physical treatment of functional neurologic disorders. In: Stone J, Carson A,

Hallett M. Handbook of Clinical Neurology , vol. 129 (3

rd

series) Functional Neurologic

Disorders. Boston, MA: Elsevier; 2016: 543-553.

5. Fobian A., Lindsey E. A review of functional neurological symptom disorder etiology

and the integrated etiological summary model. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019;44(1):8-18.

6. Perez D. Functional neurological disorders: an emerging new standard of care. Lecture

presented at: Functional (Psychogenic) Neurological Disorder: An Interprofessional

Approach; April 26, 2019; Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston, MA.

7. Espay AJ, Aybek S., Carson A., et al. Current concepts in diagnosis and treatment of

functional neurological disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1132–1141.

8. Anderson JR, Nakhate V, Stephen CD, Perez DL. Functional (psychogenic) neurological

disorders: assessment and acute management in the Emergency Department. Semin

Neurol. 2019; 39(1): 102-114.

9. Morgante F., Edwards M., Espay AJ Psychogenic movement disorders. Continuum.

2013;19(5):1383-1396.

10. LaFrance WC. Psychotherapy approaches for functional neurological (conversion)

disorders. Lecture presented at: Functional (Psychogenic) Neurological Disorder: An

Interprofessional Approach; April 26, 2019; Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston,

MA.

11. Nielson G, Stone J, Matthews A, Brown M, et al. Physiotherapy for functional motor

disorders: a consensus recommendation (long version). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.

2014; 0: 1-16.

12. Perez D. Guiding principles of treatment planning & longitudinal follow-up in FND.

Lecture presented at: Functional (Psychogenic) Neurological Disorder: An

Interprofessional Approach; April 27, 2019; Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston,

MA.

13. Nielsen G, Stone J, Edwards MJ. Physiotherapy for functional (psychogenic) motor

symptoms: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2013; 75(2): 93-102.

14. Stephen, CD. The assessment of functional movement disorders. Lecture presented at:

Functional (Psychogenic) Neurological Disorder: An Interprofessional Approach; April

26, 2019; Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston, MA.

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

20

15. Ertan S, Uluduz D, Ozekmekci S, et al. Clinical characteristics of 49 patients with

psychogenic movement disorders in a tertiary clinic in Turkey. Mov Disord. 2009; 24(5):

759-62.

16. Moore JL, Potter K, Blankshain K, et al. A core set of outcome measures for adults with

neurologic conditions undergoing rehabilitation: a clinical practice guideline. Journal of

Neurologic Physical Therapy. 2018;42:174-220.

17. Maggio J & Parlman K. Physical therapy for motor FND. Lecture presented at:

Functional (Psychogenic) Neurological Disorder: An Interprofessional Approach; April

26, 2019; Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston, MA.

18. Stone J., Reuber M., Carson A., Functional symptoms in neurology: mimics and

chameleons. Pract Neurol. 2013;13:104-113.

19. Williams C, Smith S, Sharpe M et al. Overcoming Functional Neurological Symptoms: A

Five Areas Approach. London: CRC Press; 2011.

20. Stone J. Commentary: explaining the diagnosis of functional disorders: trust,

transparency, and avoiding assumptions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family

Therapy. 2016; 37: 33-36.

21. Stone J, Edwards M. Trick or treat? Showing patients with functional (psychogenic)

motor symptoms their physical signs. Neurology 2012; 79: 282-84.

22. Nielsen G, Ricciardi L, Demartini B, et al. Outcomes of a 5-day physiotherapy

programme for functional (psychogenic) motor disorders. Journal of Neurol. 2015; 262:

674-681.

23. Jordbru AA, Smedstad LM, Klungsoyr O, et al. Psychogenic gait disorder: a randomized

controlled trial of physical rehabilitation with one-year follow up. J Rehabil Med. 2014;

46: 181-7.

24. Adams C, Anderson J, Madva EN, et al. You’ve made the diagnosis of functional

neurological disorder: now what? Pract Neurol. 2018; 18(4): 323-30.

25. Alexandra E, Jacob, MS, Darryl L et al. Motor retraining (MoRe) for functional

movement disorders: outcomes from a 1 week multidisciplinary rehabilitation program.

PM R. 2018; 10(11): 1164-72.

26. Homberg V. Neurorehabilitation approaches to facilitate motor recovery. Handb Clin

Neurol. 2013; 110: 161-229.

27. Nielsen G, Buszewicz M, Stevenson F, et al. Randomised feasibility study of

physiotherapy for patients with functional motor symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry. 2017;88:484-490.

28. Dallochio C, Arbasino C, Klersy C, et al. The effects of physical activity on psychogenic

movement disorders. Movement Disorders.2010;25:241-5.

29. Tsui P, Deptula A, Yuan DY. Conversion disorder, functional neurological symptom

disorder, and chronic pain: comorbidity, assessment, and treatment. Curr Pain Headache

Rep. 2017; 21(6): 29.

30. Gardiner P, MacGregor L, Carson A, et al. Occupational therapy for functional

neurological disorders: a scoping review and agenda for research. CNS Spectrums. 2018;

23(3) 205-212.

Standard of Care: Functional Neurologic Disorder

Copyright © 2019 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

21

31. Edwards MJ, Stone J, Nielsen G. Physiotherapists and patients with functional

(psychogenic) motor symptoms: a survey of attitudes and interest. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry. 2012; 83: 655-658.

32. MacLean, J, Ranford J. Occupational therapy for clients with functional neurological

disorders. Lecture presented at: Functional (Psychogenic) Neurological Disorder: An

Interprofessional Approach; April 26, 2019; Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston,

MA.

33. Ayers AJ. Characteristics of types of sensory integrative dysfunction. Am J Occup Ther.

1971; 25(7): 329.43.

34. Baizabal-Carvallo JF, Jankovic J. Speech and voice disorders in patients with

psychogenic movement disorders. Journal of Neurology. 2015; 262(11): 2420-4.

35. Barnett C, Armes J, Smith C. Speech, language and swallowing impairments in

functional neurological disorder: a scoping review. International Journal of Language &

Communication Disorders. 2019; 54(3): 309-20.

36. Freeburn J. Diagnosis and treatment of functional speech disorders (FSDs). Lecture

presented at: Functional (Psychogenic) Neurological Disorder: An Interprofessional

Approach; April 26, 2019; Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston, MA.

37. Hopp JL, LaFrance WC Jr. Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychogenic neurological

disorders. Neurologist. 2012; 18(6): 364-72.

38. LaFrance WC Jr, Miller IW, Ryan CE, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for

psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2009; 14(4): 591-6.

39. LaFrance WC Jr, Reuber M, Goldstein LH. Management of psychogenic nonepileptic

seizures. Epilepsia. 2013; 54 Suppl 1: 53-67.

40. Goldstein LH, Chalder T, Chigwedere C, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for

psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Neurology. 2010; 74(24): 1986-94.

41. Perez DL, LaFrance WC Jr. Nonepileptic seizures: an updated review. CNS Spectr. 2016;

21(3): 239-46.

42. Gelauff J, Stone J, Edwards M, et al. The prognosis of functional (psychogenic) motor

symptoms: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014; 85(2): 220-6.

43. Demartini B, Batla A, Petrochilos P, et al. Multidisciplinary treatment for functional

neurological symptoms: a prospective study. J Neurol. 2014; 261: 2370-77

44. McKee K, Glass S, Adams C, et al. The inpatient assessment and management of motor

functional neurological disorders: an interdisciplinary perspective. Psychosomatics. 2018;

59(4): 358-368.

45. Polich G. FND in the inpatient rehab setting. Lecture presented at: Functional

(Psychogenic) Neurological Disorder: An Interprofessional Approach; April 26, 2019;

Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston, MA.